A Marketplace of Ideas Can Only Function if People Care About What Is True.

(Audio version here)

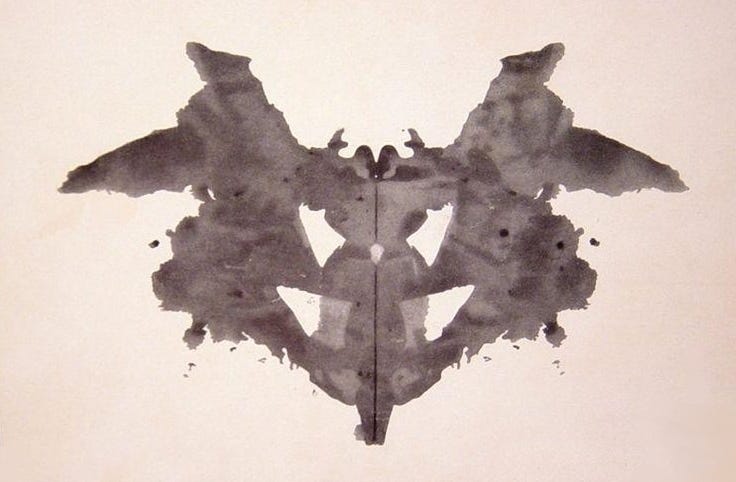

Never, in my 50 years of life, have I known a time so saturated with bullshit and awash with self-serving narratives. Engaging with the issues of the day with different ideological tribes often feels like entering entirely different realities inhabited by people who speak entirely different languages. From those on the furthest left, I am likely to hear that Keir Starmer’s Labour is a right-wing neoliberal government that prioritises the interests of businesses, cares nothing for the working class and is channelling the ethnonationalist energies of Enoch Powell. To those on the furthest right, it is a radical socialist party that positively encourages small boats to deposit black and brown migrants on our shores so it can provide them with luxury homes and a lavish income. This profound disconnect is not only seen in relation to perceptions of political parties and large cultural movements. Any politically salient current event, happening or ‘thing’ is likely to produce radically different interpretations. So consistent are these contradictory perceptions that politically charged issues are now routinely described as “Rorschach tests.”

We are certainly living through the kind of troubled and uncertain times that incline people to withdraw into their tribes and seek comfort in shared narratives of good and evil to make the world feel, at least, comprehensible. Central to this is the prominence of elements on both the left and the right who are radically distrustful of expertise, science, empirical research and reasoned argumentation, not in a productively sceptical way, but on principle. For the postmodern left, the belief is that science and reason are white, western, masculinist ways of knowing that have been unjustly privileged over other ways of knowing theorised to be those of black and brown people, non-westerners and women. Institutions and concepts of knowledge are believed to have been established to serve the interests of straight, white, western men and thus need to be decolonised. For the post-truth right, the belief is that institutions, academies and the media have been captured by ‘the elites’ who are manipulating information in order to control the masses whose common sense and lived experience is unjustly derided and dismissed. Institutions and claims of expertise are therefore presumed to serve the interests of these elites variously identified as the political left, ‘globalists’, Jews, or any of the rich and successful who don’t agree with them (Bill Gates, yes; Elon Musk, no ) and must be resisted.

It is important to note that scepticism of claims by knowledge producing institutions to be unbiased purveyors of objective truth and of specific truth claims is not only valuable but essential to a society that wishes to produce reliable knowledge. Progressives can usefully engage in empirical research to measure whether institutions of knowledge production have a bias towards white, western culture and the interests of men. They can do so without writing off science, reason and empirical research as inherently oppressive and the domain of white, western men, thus undermining research which benefits everybody and insulting everybody else. Conservatives have good grounds to claim that institutions of knowledge production, especially universities, have become politically biased in ways that undermine their ability to produce reliable knowledge. They can demand transparency, a commitment to scholarly rigour and academic freedom for a heterodox academy without becoming radically sceptical that knowledge can even be produced by scholarship. Many of both groups do precisely this, of course. I am concerned about those who do not.

Radical scepticism is inherently stultifying to knowledge production. Jean Bricmont and Alan Sokal made a useful distinction between this and specific scepticism in relation to science back in 2003,

It is important to distinguish carefully between two different types of critiques of the sciences: those that are opposed to a particular theory and are based on specific arguments, and those that repeat in one form or another the traditional arguments of radical scepticism. The former critiques can be interesting but can also be refuted, while the latter are irrefutable but uninteresting (because of their universality). And it is crucial not to mix the two sorts of arguments: for if one wants to contribute to science, be it natural or social, one must abandon radical doubts concerning the viability of logic or the possibility of knowing the world through observation and/ or experiment. Of course, one can always have doubts about a specific theory. But general sceptical arguments put forward to support those doubts are irrelevant, precisely because of their generality.

It should be clear, then, that I’m not criticising scepticism toward specific claims, nor am I suggesting that people should “follow the science” when that means uncritically accepting the pronouncements of experts as framed and presented by the dominant political orthodoxy. That would be a deeply anti-scientific stance. My concern is with those who want to abandon empirical research, scientific methods, and reasoned argument altogether, replacing them with political narratives grounded primarily in the lived experience of those understood to be oppressed by the “privileged” or “elites.” At its core, this is a question of epistemology—how we decide what is true.

Back in 2018, my American co-author, James Lindsay, commented to me that we were entering an era that could be called “Late Postmodernism - The Age of Narratives.” The postmodern worldview is defined as a ‘scepticism towards metanarratives’ among which postmodernists included trust in science, Enlightenment reason and the very concept of progress. Jean-François Lyotard argued that science, in particular, was inextricably intertwined with power and that it was always the powerful who got to ‘legitimate’ any knowledge as true. He advocated for a “parology of legitimation” in which, rather than seeking objective knowledge via the means of evidence-based epistemology and reasoned argument, we should celebrate ‘mini-narratives’ - multiple, local, community-based narratives which are all understood to have equal legitimacy.

The belief that everybody has ‘their own truth’ is at the core of moral and epistemological relativism. It need not be political at all, but instead driven by a misguided sense of woolly-headed inclusivity and avoidance of conflict. It’s not at all helpful to establishing what is true or genuinely resolving any conflict, but it is not inherently illiberal. When used for political purposes, it becomes hierarchical and moralistic and, consequently, is prone to becoming authoritarian. Then, the rationale looks like: “All claims to knowledge are equally valid but your motives are bad and mine are good/your way of knowing has been unjustly privileged and mine repressed, so we must now repress your truth claims and elevate mine.” (See Rauch’s Simple and Radical Egalitarian principles below)

When culturally dominant concepts of truth move away from “that which corresponds with reality and can be demonstrated to do so using evidence and reasoned argument” and towards “that which fits the ideological narrative of my tribe and is argued for using lived experience and victimhood narratives” we can consider ourselves to be operating within a thoroughly postmodern dynamic. We described the Postmodern Political Principle thus in Cynical Theories:

Postmodernism is characterized politically by its intense focus on power as the guiding and structuring force of society, a focus which is codependent on the denial of objective knowledge. Power and knowledge are seen as inextricably entwined—most explicitly in Foucault’s work, which refers to knowledge as “power-knowledge.” Lyotard also describes a “strict interlinkage” between the language of science and that of politics and ethics, and Derrida was profoundly interested in the power dynamics embedded in hierarchical binaries of superiority and subordination that he believed exist within language. Similarly, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari saw humans as coded within various systems of power and constraint and free to operate only within capitalism and the flow of money. In this sense, for postmodern Theory, power decides not only what is factually correct but also what is morally good—power implies domination, which is bad, whereas subjugation implies oppression, the disruption of which is good. These attitudes were the prevailing mood at the Sorbonne in Paris through the 1960s, where many of the early Theorists were strongly intellectually influenced.

Because of their focus on power dynamics, these thinkers argued that the powerful have, both intentionally and inadvertently, organized society to benefit them and perpetuate their power. They have done so by legitimating certain ways of talking about things as true, which then spread throughout society, creating societal rules that are viewed as common sense and perpetuated on all levels. Power is thus constantly reinforced through discourses legitimized or mandated within society, including expectations of civility and reasoned discourse, appeals to objective evidence, and even rules of grammar and syntax. As a result, the postmodernist view is difficult to fully appreciate from the outside because it looks very much like a conspiracy theory.

I do not mean, of course, that the populist right (or even much of the woke left at this point) is reading Foucault, Lyotard and Derrida and using their work to inform their philosophical stance on how knowledge works. Counter-Enlightenment thought has long existed on both the right and the left and, indeed, precedes the Enlightenment. It was the uncritical acceptance of dominant cultural narratives held tribally, moralistically and emotionally that Enlightenment thought arose to challenge with its arguments for evidence, reason, individual thought and specific scepticism. Postmodernism was simply the strand of Counter-Enlightenment thinking that gained traction and social prestige and influence and, I would argue, provided fertile ground for a wider range of Counter-Enlightenment views to seed themselves in, including illiberal right-wing populism. It is the epistemological and political similarities between these two movements which have led so many people, primarily on the evidence-based, liberal right, to coin the term ‘woke right’ to describe it. While postmodernism is (rightly) largely understood to be a movement associated with the political left, at its root it refers to a radical scepticism of what it describes as ‘metanarratives’ but can often be understood as foundational principles of Western modernity like ‘science’, ‘reason’, ‘liberalism’ and ‘progress,’ and the advocacy of small, local narratives founded in emotional, moralistic stories justified by politically-biased lived experience.

Postmodernism is often described as a form of fragmentation where people break away from holding a common concept of truth as correspondence with reality and reason as a way to reach sound conclusions and splinter into tribes based on shared emotionally resonant political narratives. The rise of social media has, of course, facilitated this development hugely, The Australian filmmaker, Mike Nayna, described the result of this as the formation of ‘truth denominations,” in 2021, saying,

In an environment of abundant information, people craving consistent perspective cluster into truth denominations. Worldview proof goes viral within these hermeneutic tribes & works like valium for dissonance.

It is particularly frustrating for those of us who have long been criticising this development on the woke left, to see others among the ‘anti-woke’ who are on the right and had made good criticisms of the irrationalism and resistance to evidence on the left then seemingly embrace it when it emerges on the populist right.

As Katherine Brodsky put it bluntly:

“Spin” is hardly new, of course. Rhetoric, not to mention downright sophistry, has been central to human intellectual thought for at least as long as anybody has been writing it down. Motivated reasoning and confirmation bias are part of the human condition that, with the best will in the world, we can none of us hope to escape entirely, (and we don’t all have the best will in the world). We expect news outlets to have a bias and we can detect what they are and be sure to read a variety of them across political lines. We expect our politicians to engage in spin in favour of their own party and against the opposition and, even though we might wish the political system did not work like that, it can also be useful to see the most positive and most damning interpretations of any policy, statement or action. After all, we are intelligent adults capable of recognising well-evidenced sources, well-reasoned arguments and sifting through a variety of interpretations to exercise our own judgement and form our own conclusions, aren’t we? Aren’t we?

For some time now, I have been asking myself if I am actually that most abominable thing one can be considered to be - an elitist. I increasingly find myself surveying my fellow humans engaged in discussion and debate on issues of political and cultural importance and wondering how a species of such stupid, irrational and aggressive apes has not yet made itself extinct. We are equipped with brains big enough to have ventured into space, eradicated smallpox and set up complex social, political, legal and economic systems that have achieved levels of human thriving never before seen. We have unprecedented levels of literacy and instant access to information about almost everything and a wide range of analysis of it all. Yet a significant proportion of us seem to prefer to remain within a narrow ideological tribe defined by a simplistic shared narrative while throwing the virtual equivalent of faeces at each other. Is the problem simply that a large proportion of the population is very stupid? Am I suggesting some kind of ‘philosopher kings’ solution, entirely against my liberal democratic principles?

But, no. The problem is not one of intelligence, but of epistemology, principle and attitude to engagement. “Philosophers”, or the contemporary version of this - intellectuals or experts - are by no means guaranteed to care about what is true, value sound and consistent ethical reasoning and engage with others who disagree with civility, intellectual honesty and charity. On the “post-truth right”, we are likely to see the same person who could well put humans on Mars engaging in a never-ending stream of ideologically biased falsehoods and calling people with whom they disagree childish names like “pedo guy.” The opposition to truth, reason and civil engagement in robust debate on the postmodern academic left is one I have dedicated a decade to addressing in detail.

The problem is that our expectations of public discourse and debate on all levels have dropped considerably. Without an expectation that arguments will be reasoned, truth claims will be evidenced, ethical principles will be held consistently and debate will be civil, we cannot have a functioning Marketplace of Ideas.

First published in 1993, Jonathan Rauch’s Kindly Inquisitors, which I continue to consider the essential primer to our ‘truth’ problem and to have only become more valuable with time, addressed this rising threat to this expectation. Rauch was writing at precisely the time that what James Lindsay and I, 25 years later, called ‘applied postmodernism’ was bursting onto the intellectual scene. He wrote:

To the central question of how to sort true beliefs from the “lunatic” ones, here are five answers, five decision-making principles—not the only principles by any means, but the most important contenders right now:

The Fundamentalist Principle: Those who know the truth should decide who is right.

• The Simple Egalitarian Principle: All sincere persons’ beliefs have equal claims to respect.

• The Radical Egalitarian Principle: Like the simple egalitarian principle, but the beliefs of persons in historically oppressed classes or groups get special consideration.

• The Humanitarian Principle: Any of the above, but with the condition that the first priority be to cause no hurt.

• The Liberal Principle: Checking of each by each through public criticism is the only legitimate way to decide who is right.

Only the last of these, Rauch argued, was fit for a pluralistic society trying to approach truth. Yet it is precisely this liberal principle that has lost ground. In order to facilitate the checking of each by each through public criticism in order to establish what is true, we must have a Marketplace of Ideas that functions on those evidence and reason based rules of engagement.

Critics of liberalism have long argued that the concept of a Marketplace of Ideas as a way for bad ideas to be defeated by better ones is naive. Surely it relies upon the idealistic assumption that humans are objective, rational agents who will evaluate ideas for soundness of argument and provision of evidence when the reality is that we are much more likely to go with the ideas that resonate most with our own moral intuitions and what we’d like to be true? Well, yes and no. Liberals are not (generally) that naive and have already thought of that. This is where the ‘expectations’ part comes in. As the social psychologist, Jonathan Haidt, has argued,

[E]ach individual reasoner is really good at one thing: finding evidence to support the position he or she already holds, usually for intuitive reasons. We should not expect individuals to produce good, open-minded, truth-seeking reasoning, particularly when self-interest or reputational concerns are in play. But if you put individuals together in the right way, such that some individuals can use their reasoning powers to disconfirm the claims of others, and all individuals feel some common bond or shared fate that allows them to interact civilly, you can create a group that ends up producing good reasoning as an emergent property of the social system.

That is what the liberal Marketplace of Ideas looks like. I keep reiterating the liberal marketplace of ideas because some kind of marketplace of ideas will exist as long as humans exist and keep having ideas, buying into ideas and selling others on ideas and the ideas which predominate in a society shift and change as a result of this. The rules and expectations that govern that marketplace of ideas can vary hugely and they need not be that the ideas are well-argued to be true. They very often have not been. For most of history, the driving force has been narrative coherence, emotional appeal, or alignment with power. People weren’t rewarded for being right and certainly not for spotting errors or ethical inconsistencies in the prevailing orthodoxy. They were rewarded for compliance with whichever narrative the current warlords, monarchs or theocrats had mandated adherence to. The development of WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) societies and the concept of the liberal Marketplace of Ideas was an anomaly which mitigated the human tendency to prefer satisfying stories over complex reality and engage in motivated reasoning to make them work rather than changed it. Nevertheless, it did become an expectation that people will accept the right of ideas they disagree with to exist and at least try to make a case for their own that is grounded in reality and makes sense if they want to be taken seriously, and knowledge as well as human rights advanced astonishingly fast.

Without the expectation that people will put forward their own ideas in evidence-based and reasoned ways and accept evidence-based and reasoned critique of them, we cannot establish what is true. We descend instead into a war of tribal narratives where nothing can be established as true because truth is not what is being sought. Rather, combatants duel to establish their own narrative as morally superior and proponents of other narratives to be morally bankrupt. Rather than convince onlookers of the veracity and principled consistency of their arguments, they seek to gain moral and social prestige and make dissent socially costly.

We have been losing this expectation for some time now. Some people are inclined to blame this entirely on the rise of the internet. Humans are motivated to seek community with those with whom they, as Haidt put it, “feel some common bond or shared fate that allows them to interact civilly.” Within the real life geographical communities in which we have historically lived, we are likely to find people (whom we fully see as people) with a variety of ideas and that naturally acts as a moderating force. Behaving uncivilly comes at a social cost, because one cannot easily move home if one has alienated everybody. Online, we can easily find communities who already agree with us on everything, no matter what that may be, and, if people become unpopular within it, they can easily just find another, especially if they engage anonymously. This has certainly hugely exacerbated the ‘truth denominations’ problem and we would all do well to limit our social media usage.

Nevertheless, the problem preceded this development and expands beyond it because it is rooted in human psychology and our preference as a species for comforting narratives that support what we already believe and not a cold, hard dedication to truth and consistent principles. We needed to set up systems to mitigate this tendency and enable people with different ideas to engage with others and exercise a form of collaborative combat to “produc[e] good reasoning as an emergent property of the social system.” As the expectation to back up truth claims with evidence, present reasoned arguments and engage with those with whom one disagrees in a civil manner (if one wishes to be taken seriously and respected) has waned, we see the impact of this on institutions of all kinds and in public discourse more broadly.

Addressing this problem is going to be extremely difficult. Institutions of knowledge production can play a significant role here by committing to upholding viewpoint diversity and an expectation of reasoned and evidenced argument, as can mainstream media. We should expect them to do so and do so transparently. This cannot entirely resolve the problem, however. We have seen the rise of ‘alternative spaces’ like the ‘heterodox’ ‘anti-woke’ and ‘gender critical’ spaces to counteract the increasing ideological blinkeredness of mainstream spaces. We have also seen the rise of much darker spaces like ‘incel’ forums and ‘groyper’ communities. We cannot control the proliferation of such spaces, nor, unless they are coordinating violence or other criminal activity, should we try to do so. Mainstream institutions and media can best minimise the extent to which alternative spaces are needed and dark, twisted and conspiratorial ones are attractive by keeping a wide range of views speakable within themselves and committing to high standards of factual accuracy and transparency.

Ultimately, we can only reverse this worrying trend away from caring about what is true, reasoned and consistently principled by changing our culture. This is a much more complex and multi-faceted task, but we can all play a role in it. Much of the problem we are currently facing stems from a cultural shift in which people are simply less worried about saying things that are untrue or unreasonable or uncivil because they know that this will not negatively impact their reputations among their tribe. We need to ensure that it does negatively impact their reputations and we can do this most effectively by taking on illiberal and irrational elements of our own tribes or overlapping with our own tribes.

It is illiberal to make it socially costly to hold the “wrong” beliefs when this manifests in ‘Cancel Culture’ style penalties for dissent - social media pile-ons, calls for firing, pressuring platforms to engage in no-platforming, character assassinations involving misrepresentation and smear tactics etc. It is fully in keeping with liberal principles, however, to hold in high esteem those who engage civilly with reasoned and evidenced arguments (even if you disagree with them) and to lose respect for those who are abusive, irrational and care nothing for what is true (even if you share their end goals). As social mammals, we care deeply about being respected by those whom we ourselves respect. Consequently, we can effect social change by choosing whom we respect carefully and doing so on criteria which include engaging with others politely and in good faith, demonstrating a commitment to what is true and endeavoring to make sense. If a sufficient number of people on the political left had upheld these standards and allowed those who did not to fall in their estimation, the woke left could not have gained traction. If ethical conservatives who value evidence, reason and civil but robust debate uphold these standards now, they can hold back the illiberal, populist right from gaining any more social power and prestige and further degrading the standards of public discourse.

We need a culture where saying untrue, unreasoned or abusive things damages an individual’s reputation among their own political or cultural tribe whether that individual is a political pundit, an academic, a politician or a private individual. The danger on the left lies in the spread of postmodern suspicion of truth and objectivity as the property of ‘the privileged’ imposed oppressively on the marginalised. The danger on the right lies in the gleeful embrace of post-truth, in which lying is seen not as disqualifying but as a power move struck against ‘the elites’ by the disenfranchised masses. Both trends insult the intelligence and ethics of those they claim to speak for and seek to dismantle the shared epistemic standards which have enabled the formation and norms of liberal democracies which so many now take for granted.

We do not need everybody to agree. We do not need everybody to be an expert on every subject. We do need a shared expectation of how one earns credibility in the various arenas of knowledge production and in public debate. Without that, the liberal Marketplace of Ideas dies. And when it dies, the philosophical underpinnings of Western modernity and the very concept of truth go with it.

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain goes out to nearly 5000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.6% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2025 is to increase that to 7%. This will enable me to keep doing this full-time into 2026! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

There isn’t enough time between assaults to be considered. Social media is constant. As the Very Online become Even More Very Online, the battle becomes a never ending one. It triggers what looks an awful lot like PTSD to me. I’ve seen the same symptoms in combat veterans who came back to our unit from Desert Storm - hypervigilance, paranoid theories about ‘the other’ that were firmly based in a lived reality that is no longer relevant in garrison, an attachment to fellow combatants that transcends any facts (because their lives literally depended on one another - the ultimate character test; everything else is small stuff).

The Very Online Left and the much smaller Very Online Right both show signs of this. The abandonment of principle is a side effect. If we want the world to recover, we’d need to change social media in some fundamental way.

Don’t know what you’re on about saying “The right is not demonstrating any aversion to real truth” when the entire policy of the trumpist regime is “alt facts,” lies as strategy (“I actually won in 2020” & “they’re eating the dogs”), and “blame it on the other guy”? Slight nod, also, to strange religious tenets (virgin birth, resurrection from the dead, etc). Well I don’t expect someone with a profile pic of a guy picking his nose to argue reasonably & respectfully so 🤷♀️