"I Disagree With This Person, But Support Their Right To Speak"

A Diluting Disclaimer or a Bridge-Building Expression of Principle?

(Audio version here)

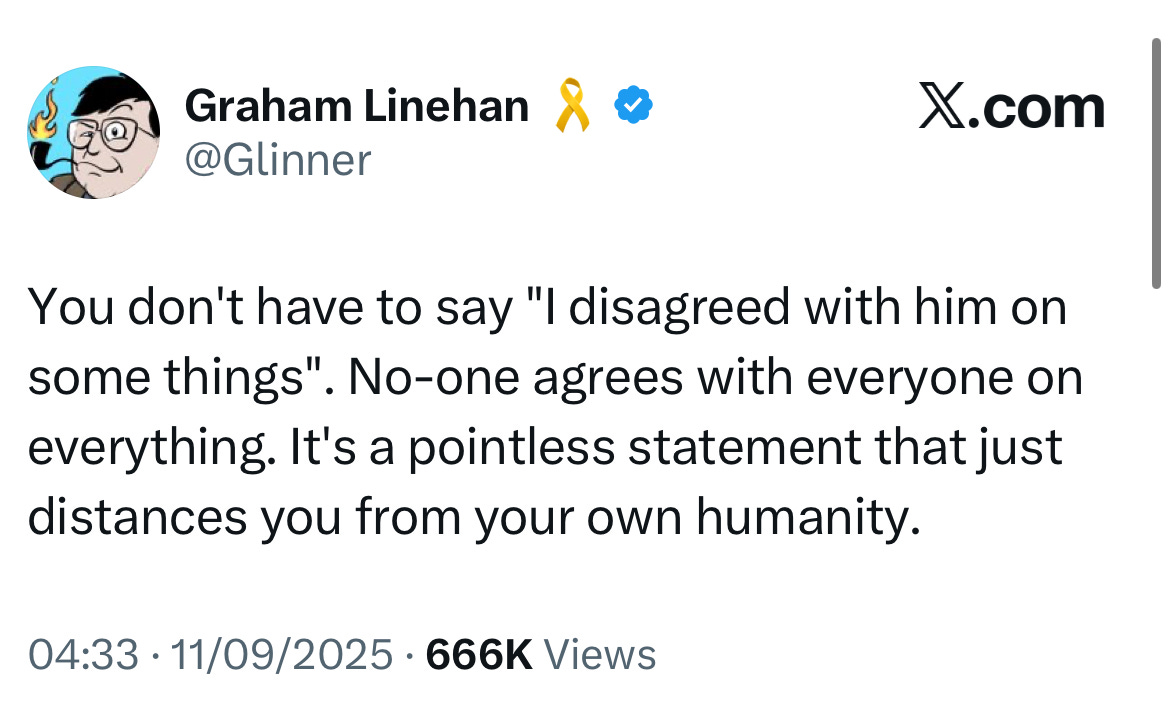

I recently disagreed with Graham Linehan on X. Graham was referring to the murder of Charlie Kirk. He felt that referring to one’s disagreement with Mr. Kirk’s political positions while deploring his murder detracts from the simple human empathy and outrage at the taking of a man’s life. I thought it was important that political opponents of Kirk’s were seen to condemn the actions of the murderer who was almost certainly also a political opponent.

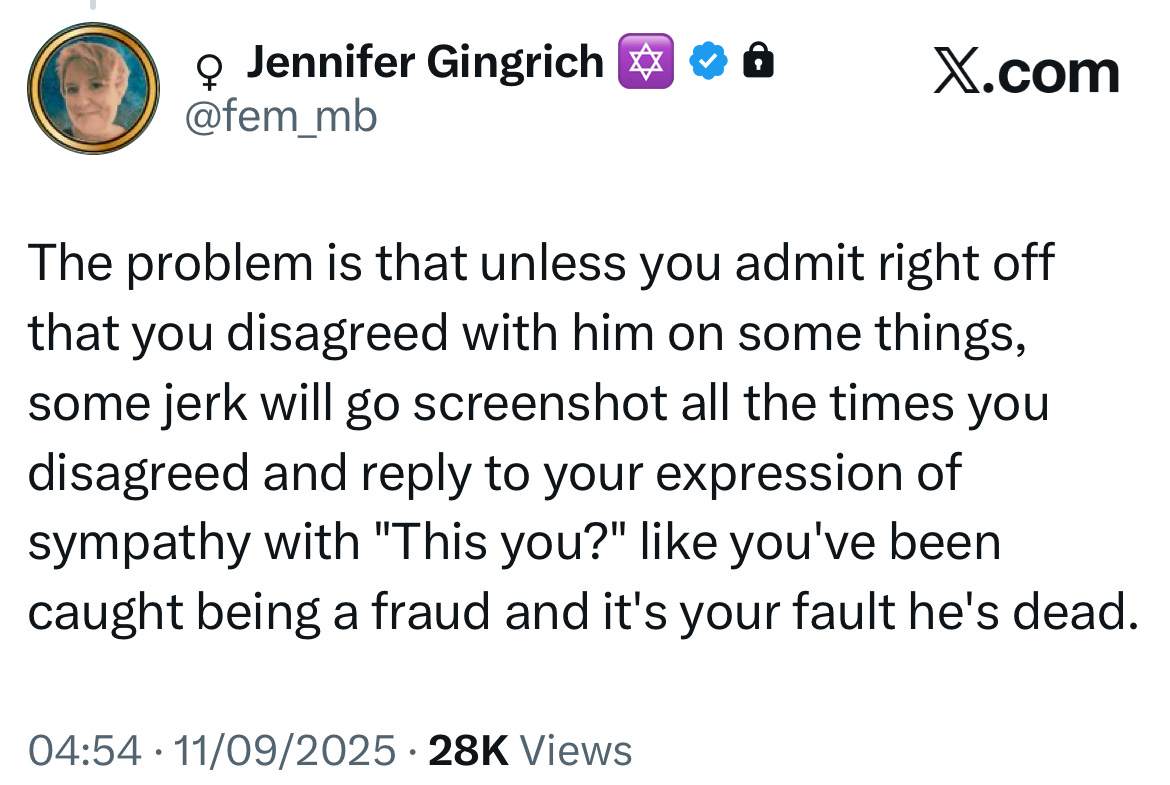

Several people commented thoughtfully, disagreeing with me and referencing the pressure that people can often feel to signal disagreement with someone whose right to speak without facing penalties, including violence, they are defending. This confused me a little at first. I don’t need pressuring to be clear that I disagree with anyone. I am permanently ready to say so! I am highly disagreeable! More seriously, I see real value in stating a variation on “I disapprove of what you say, but I defend to the death your right to say it” and I actively encourage people to do this more visibly.

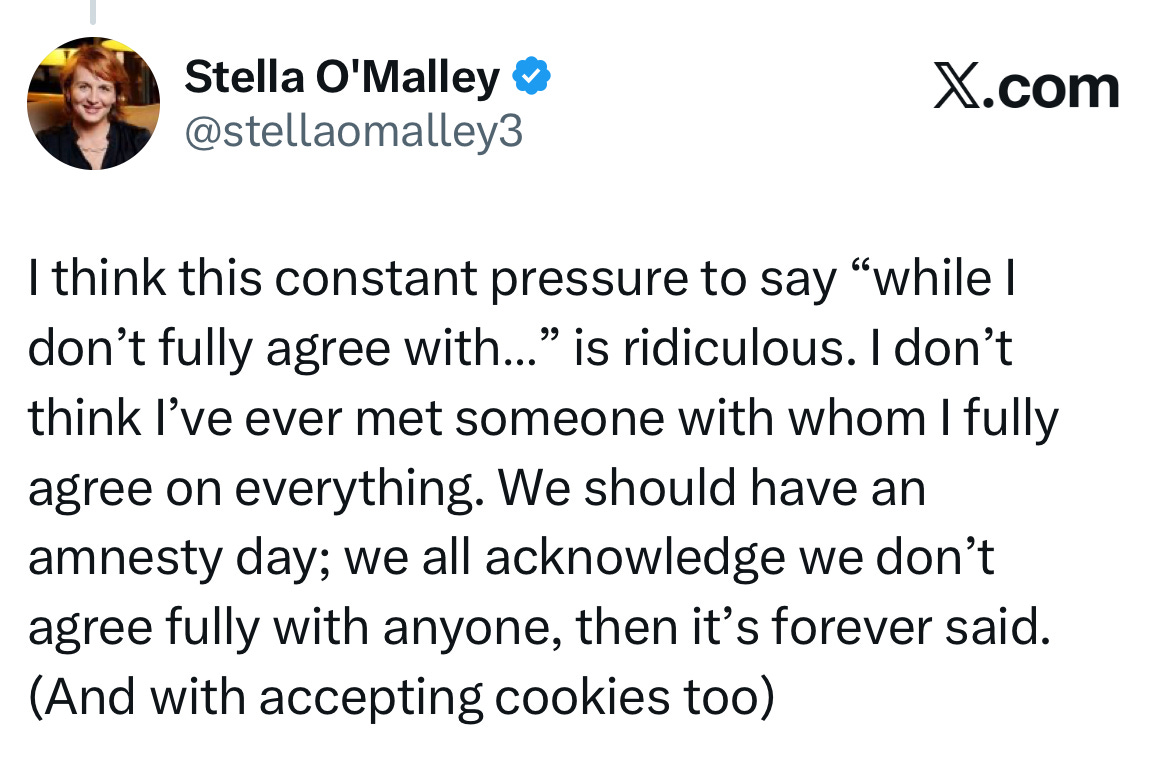

Nevertheless, it is clear that many people whom I know to support liberal principles, see value in viewpoint diversity and be actively involved in organising public debate where people can air their disagreements have a different interpretation of, “I disagree with this person, but…’ to me.

Here, Stella and Abhishek clearly feel that declaring disagreement before supporting somebody’s right to speak detracts from, qualifies or ‘dilutes’ the expression of support for freedom of speech. Stella is the founder of Genspect and focuses on the material impact of shoddy, ideologically-biased approaches to gender medicine on young people. I know her to face constant demands to justify her decisions about speakers on this issue on the grounds that they have, at some other time and in some other place, said something which could be interpreted as problematic in some way. This gets in the way of having productive discussions about anything and working towards effecting practical change. In this context, I am entirely in support of the desire to accept that people will disagree on all sorts of things without feeling the need to state all the disagreements, justify them or reconcile them before discussing important issues.

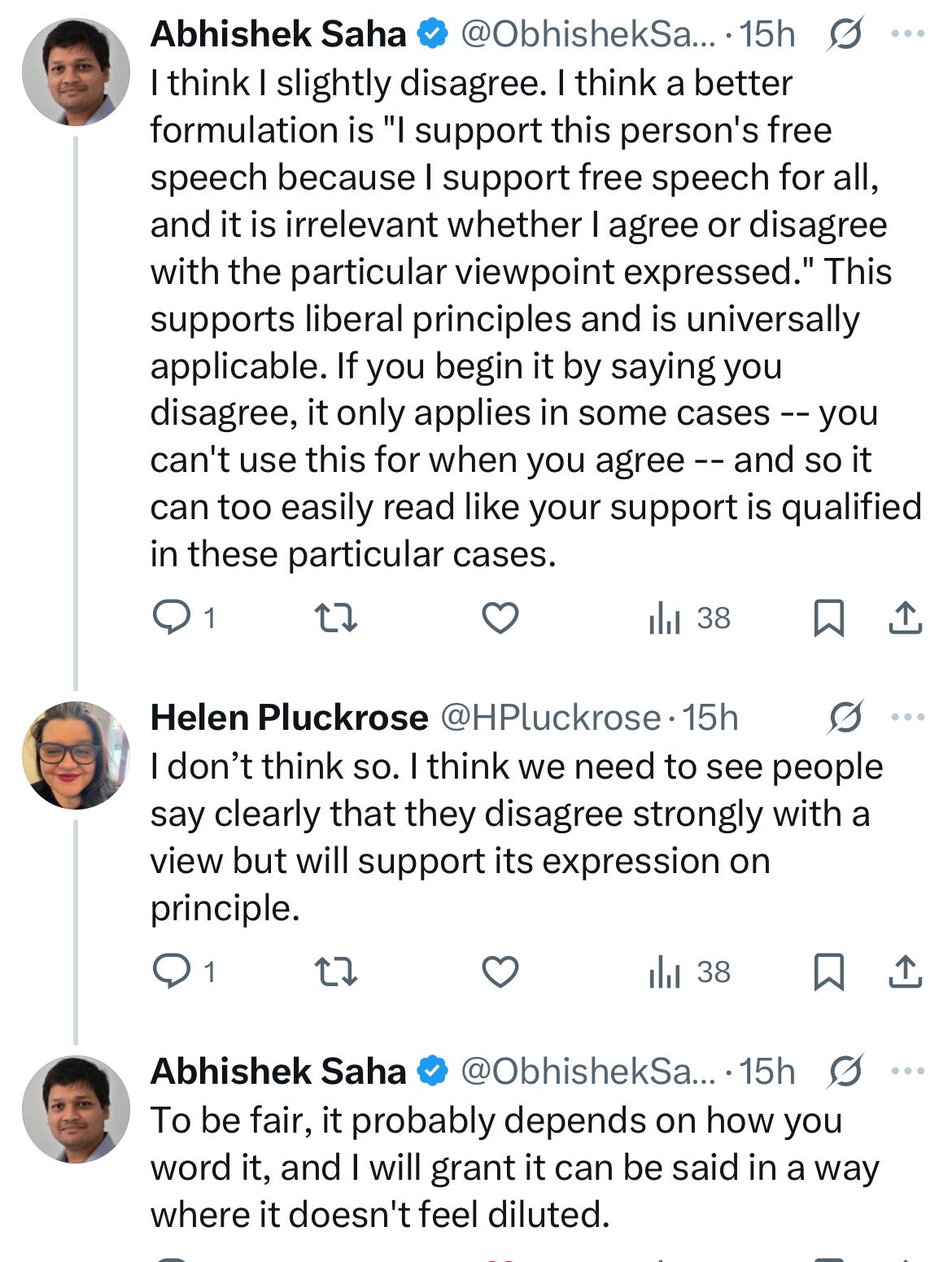

Abhishek is a mathematician and founder of London Universities Council for Academic Freedom and a co-convener of Academics for Academic Freedom. To him, “I disagree with this person, but…’ presents an unnecessary qualification to the core issue - the defence of freedom of speech. By adding this clause, we risk diluting that principle and adding variables that do not need to be there, detracting from the principle that people must be able to express their views, regardless of whether or not we agree with them. I can see this argument too. That is the core issue and it does not need qualifications. We can and should stand by it consistently.

These are two good objections to the phrase, “I disagree with X but…” Both of them reflect the tribalistic problem where so many assume that if you defend someone’s right to speak, you must agree with everything they say. People really can feel pressured to make this statement as a self-protective disclaimer to mollify a mob or to qualify their defence of free speech. This gets in the way of effective organisation and collaboration and risks diluting the strong principle of free speech in which one’s own agreement or disagreement is irrelevant.

Nevertheless, I am going to defend the use of the phrase. I do believe it is essential to uphold the principle of free speech consistently regardless of whether one agrees with it and I reject the fallacy of “guilt-by-association” which can lead people to feel they must issue disclaimers when doing so. I still see value in explicitly and visibly defending the speech of those with whom we disagree.

My writing focuses on liberal approaches to addressing the culture wars and overcoming the polarisation that currently plagues us. Key to the polarisation problem is the belief that so many have that their political opponents typically hold much more extreme and illiberal views than they really do. This leads to a feedback loop where people see their political opposition not simply as disagreeing with them but as being their enemy; not simply as wrong in ways that matter for the health of our societies, but evil in ways that threaten to destroy those societies. This distorted perception is exacerbated by social media.

These dynamics take political disagreement into the realm of existential crisis and enable people, including the political leaders whom we elect, to justify authoritarian responses to their political opponents. Reducing polarisation and simmering down the heat of the culture wars, therefore, requires addressing this misconception. As social psychologists, Michael Pasek and Samantha Moor-Berg have demonstrated, “Learning your political opponents don’t actually hate you can reduce toxic polarization and antidemocratic attitudes.” One very good way to convey this message is for as many liberals as possible on both sides of political spectrum to be seen to defend the freedom of speech of those with whom they disagree politically and unambiguously condemn political censorship and especially violence, particularly on social media.

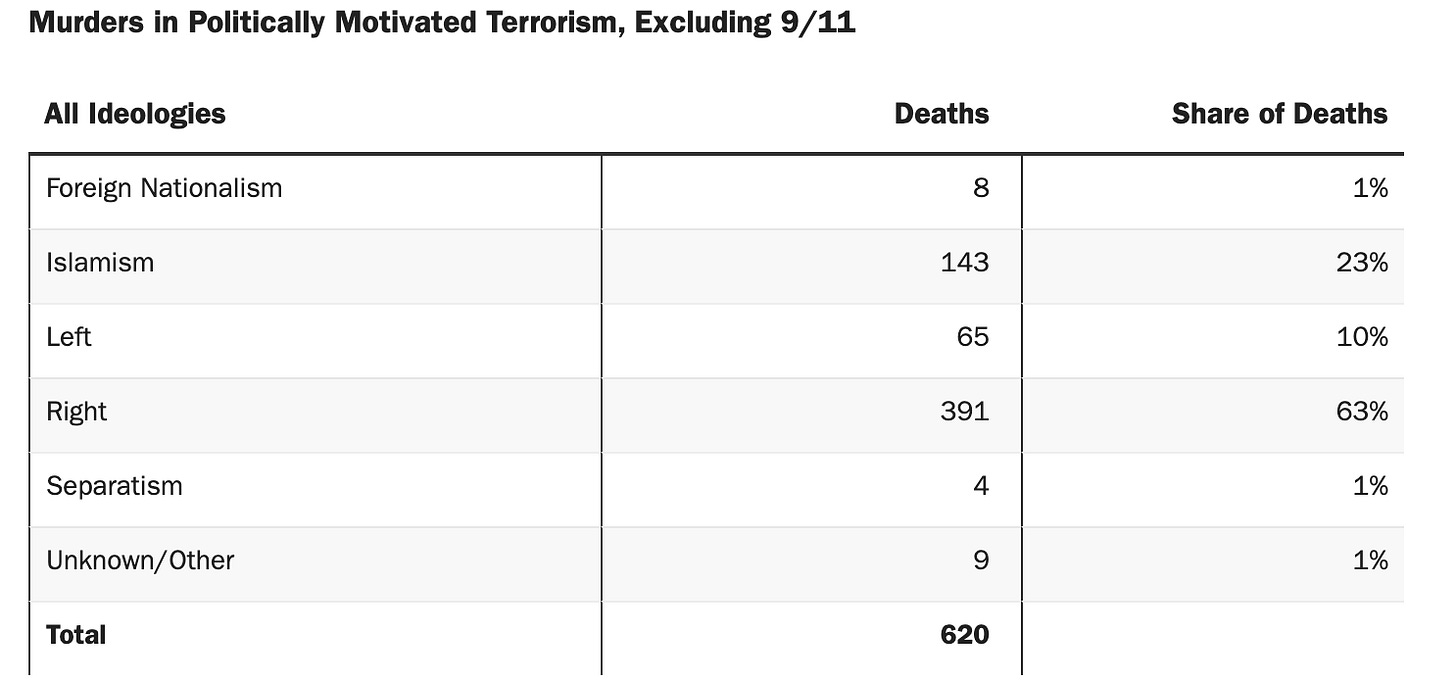

Never has this been more important than right now, in the aftermath of the murder of Charlie Kirk. Rhetoric from the illiberal right, including the president of the United States, the vice-president and Elon Musk, informs us that ‘the left’ is characterised by its support of political violence. Many on the left have responded to this claim with evidence from the libertarian Cato Institute that the majority of political violence is perpetrated by extremists on the right.

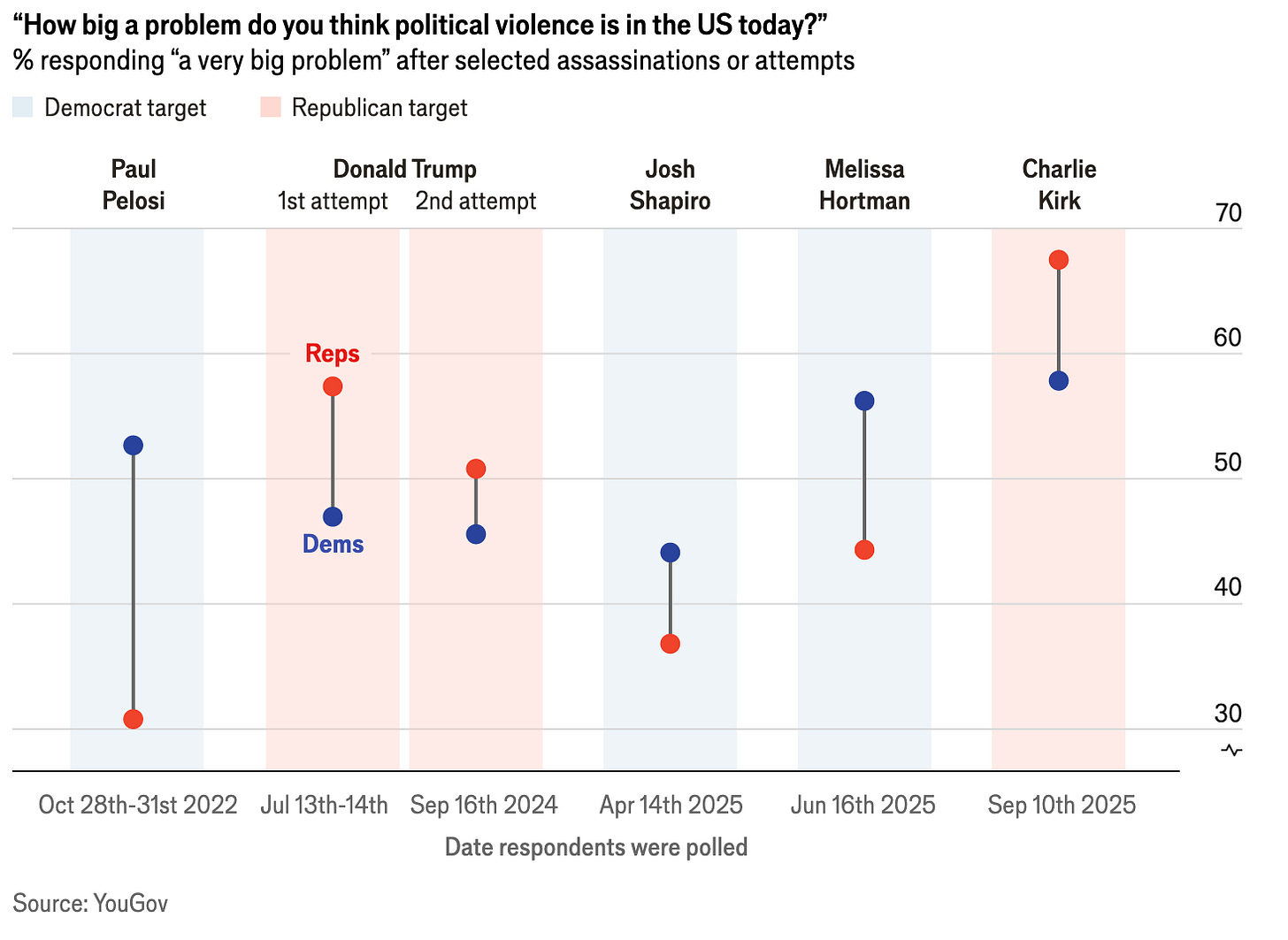

This matters. We need to know which ideologies and political positions are driving support for political violence so that we can address it effectively. We should be concerned that polls have shown significantly more endorsement of political violence coming from people on the left, particularly young ones, and also that more actualised political violence comes from the right. We should also be aware that polling can produce highly variable results depending on what is happening in the news cycle. Support for political violence is likely to be highly overestimated on both sides of the political spectrum.

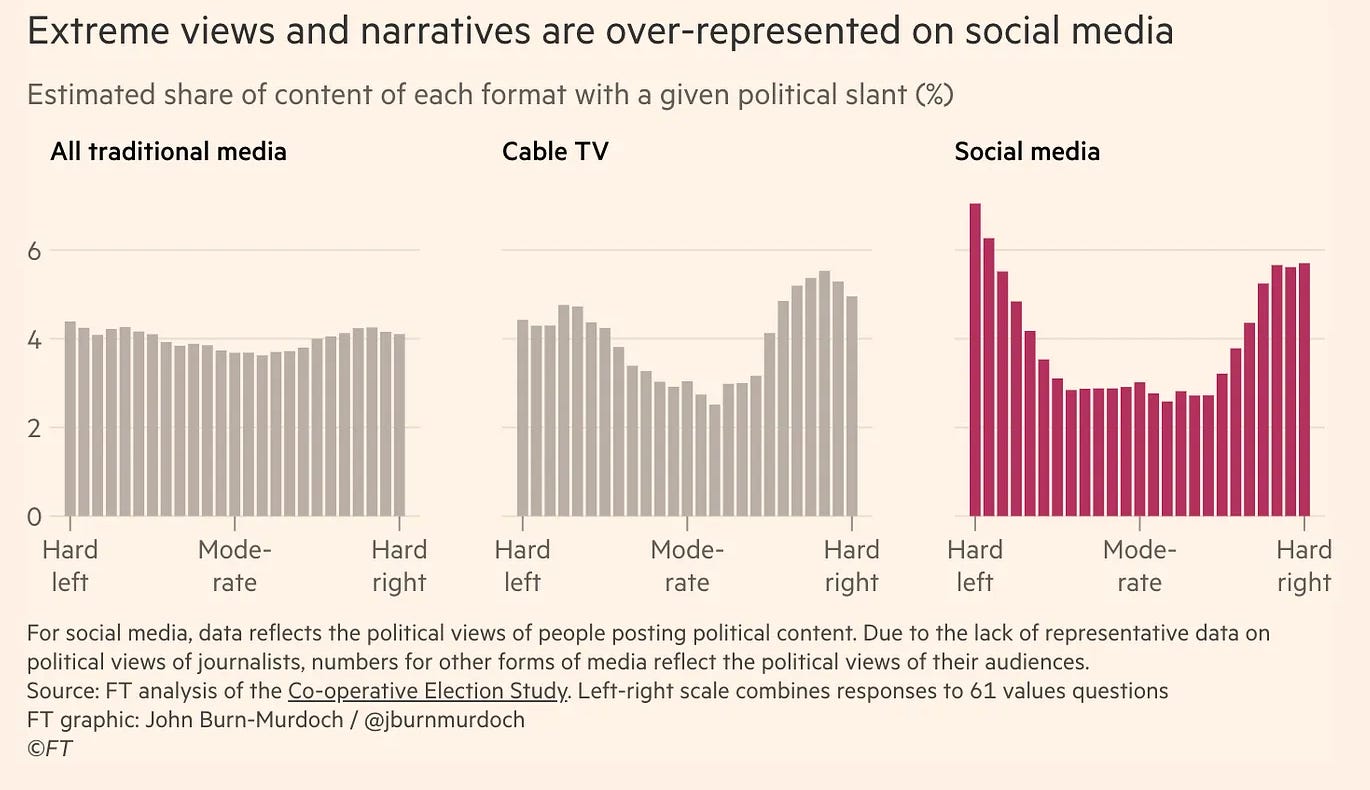

This is all deeply worrying. Illiberal extremists on both sides of the political spectrum, aided by the function of social media, hold significant sway over political discourse. They create a false impression that people generally are much more illiberal and extreme than they really are. When we consume only media dominated by algorithms which present us with highly partisan narratives tailored towards our own political biases, we are liable to come away with the impression that the ‘other side’ is totally dominated by extreme illiberalism and even wants us dead. This strongly incentivises the abandonment of one’s own liberal principles and the endorsement of counter-authoritarianism. It influences not only how we interact on social media, but how we engage with each other in real life and, most importantly, the kinds of political leaders we are likely to elect. Contrary to the oft-cited slogan “Social media is not real life,” it does indeed have significant power to affect our real lives.

Many liberals are currently feeling hopeless about the current situation and the job of holding back the tide of increasing political hostilities and polarisation and even civil war. It can feel as though there is nothing we can do and that we are shouting futilely into a void about the need to respect freedom of belief and speech and oppose authoritarianism and extremism consistently while the world is exploding around us. Yet, we can each make a decision not to contribute to this, especially on social media. Instead, we can be visibly and vocally in support of the rights and freedoms of those with whom we disagree and utterly opposed to censorship and especially to political violence.

We are a reciprocal species. This drives both our best qualities of cooperation and empathy across divides and our worst ones of inter-group hostility and tribalism. We have a drive to meet other people where they are and to return to them the kind of treatment they mete out to us. When our social media algorithms or our political leaders are telling us the other side hates us and means us harm, we are extremely likely to develop attitudes towards them that are hateful and harmful. This may well benefit authoritarian political leaders who can use our fear and corresponding willingness to allow them to betray the freedom principles underlying our societies, but it is terrible for us and the liberal democratic future of those societies.

Culture wars are ultimately about culture and culture is something we can all contribute to for good or for ill. We can trigger reciprocal enmity and polarisation by throwing out hateful and hostile messages and condemning the entirety of the other side as evil and complicit in existential societal harm. We can also not do that and instead inspire reciprocal empathy and a will to find common ground by consistently being seen to defend the freedoms and the humanity of those with whom we disagree. The statement, “I disagree with what this person says, but I support their freedom to say it and I utterly condemn attempts to silence them with political violence,” when used in this context, is an important part of that. Do not be afraid to say it.

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has over 5000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.75% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2025 is to increase that to 7%. This will enable me to keep doing this full-time into 2026! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

I think this is one of those issues that I could not be more convinced that both sides are equally right.

Let us assume one is a militant leftist atheist who disagrees with most of what Kirk stood for.

I believe that it is perfectly sensible to signal one's disagreement before expressing sorrow and support for free speech, partly to ensure that you are not seen as a Kirk supporter by fools, and partly to emphasize that free speech is for everyone.

On the other hand a man has died. One should be able to express sorrow and support for free speech with no further words, caveats, buts, excuses or opinions. Anyone sensible reading one's expression of sorrow and support and should take that at face value in the knowledge that it is utterly irrelevant whether one supports or does not. The shooting of an advocate of freedom of speech is something that requires the expression of sorrow and the expression of support for free speech. It does not require anyone to know whether one is a communist, literal nazi, or anywhere in between.

I think it's a very valid and useful qualification. 50 years ago the principle was mainstream and widely accepted as a core tenet of our democracy. It clearly no longer is, and hasn't been for some time. It needs restating often - especially by our politicians - and re-establishing as a core value, now more than ever.