In Defence of Reading Crap

Not all reading needs to be “improving”

(Audio version here)

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has over 6000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.8% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2026 is to increase that to 7%. This would enable me to write full-time for my own substack! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

There have always been those who sneer at others for reading light, contemporary fiction, considering this to be mere escapism devoid of intellectual value. Likewise, there have always been those who express self-righteous condemnation of people reading books considered salacious, impious or otherwise immoral. Historically, these concerns have often been targeted at women primarily, accompanied by fears that we are particularly prone to developing unrealistic expectations, getting lost in fantasy worlds or irreligious superstition or becoming morally corrupted.

When the Western novel emerged in the early modern period, there was much moral debate about whether these “romances” were, in fact, just a form of lying. It seemed to many that there was no value and even something immoral about people making up stories of things that never happened or reading those written by others purely for the enjoyment of it. Once it was established that people were going to do this anyway and fiction was not going away, the word ‘improving’ started to be used to qualify books. An ‘improving book’ was one which educated one on serious matters, built character or advanced one’s theological knowledge or piety. The implication was that other kinds of books were, at best, worthless and, at worst, degrading.

Some of our greatest historical novelists themselves displayed concerns about the value of their own fiction and the morality of writing it. Charlotte Bronté, aged 20, became concerned about her own creative imagination and wrote to the poet laureate, Robert Southey, for advice about it. He responded,

There is a danger of which I would with all kindness & earnestness warn you. The daydreams in which you habitually indulge are likely to induce a distempered state of mind, & in proportion as all the “ordinary uses of the world” seem to you “flat & unprofitable”, you will be unfitted for them, without becoming fitted for anything else. Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life: & it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure she will have for it, even as an accomplishment & a recreation. To those duties you have not yet been called, & when you are you will be less eager for celebrity. You will not then seek in imagination for excitement.

Bronté, at first, determined to take this advice, but fortunately for us, could not suppress the urge to write.

The concern that women, in particular, were vulnerable to developing a distempered state of mind if they read too much fiction or fiction that was too sensational or salacious appears in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. In this, the 17-year-old heroine, Catherine Morland, is hooked on the Gothic novels of writers like Ann Radcliffe and imagines herself to be surrounded by dark and sinister mysteries. She is ultimately brought to her senses by confrontation with the much more mundane reality of human meanness and injustice and becomes a woman of common sense who holds her imagination in check. Austen was no misogynist and presents the frailties of both men and women with an ironic humour but she too seems to have accepted that women are particularly prone to getting carried away.

We no longer hear these particular concerns so explicitly expressed but we continue to have a rather contemptuous attitude to what could be considered ‘misuses of the imagination.’ We still draw dividing lines between which uses of it are considered legitimate and worthwhile and which are not. We still have the concept of ‘improving.’

In the case of men, the main concerns appear to be pornography and video games. Beyond legitimate concerns about ensuring consent of porn actors, the concern is that they develop an unrealistic attitude towards sex and one that demeans and even endangers women. They might even stop wanting to have relationships with real women and lose interest in more productive life goals. Men’s enjoyment of video games is frequently contemptuously presented as childish time-wasting which could be spent improving valuable skills, having meaningful social interactions or reading (improving?) books. The idea that solitary downtime engaged in an absorbing hobby could be worthwhile in itself is typically dismissed by video game critics.

For women, the primary concerns with their misuse of their imagination have been the pressure to curate an imagined perfect life on social media platforms like Instagram rather than actually living a normal, healthy and productive one and indulgence in light fiction, romantic fiction and erotic fiction. There are valid concerns around pressure to be “Instagram Perfect” and accompanying dissatisfaction with the realities of life and damage to the self-esteem, although the poison there is likely in the dose. Concerns about women’s enjoyment of easily consumable fiction is much harder to justify. Yes, we could all spend our spare time reading works of great literary fiction, but the benefits of curling up and losing oneself in a good book, for either sex, should not be underestimated.

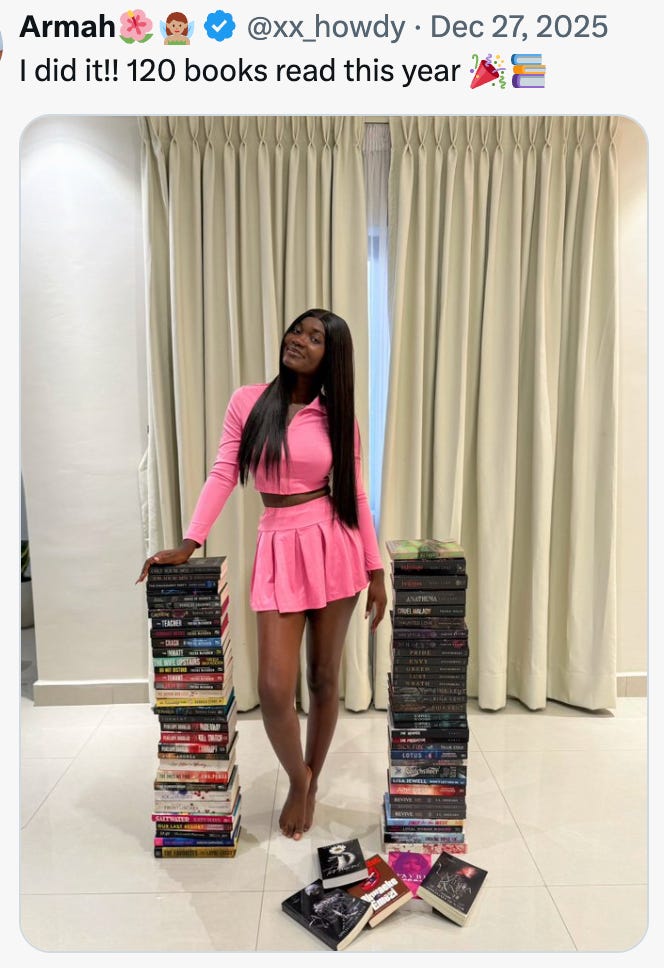

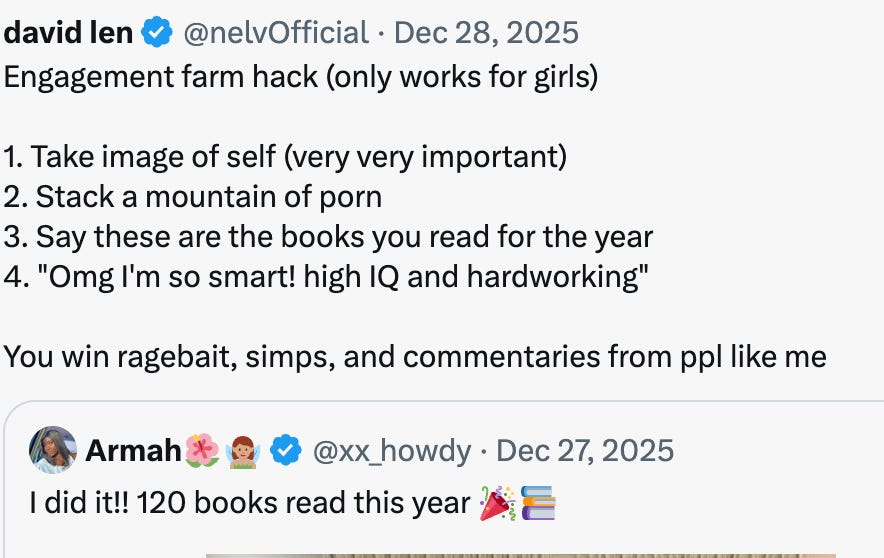

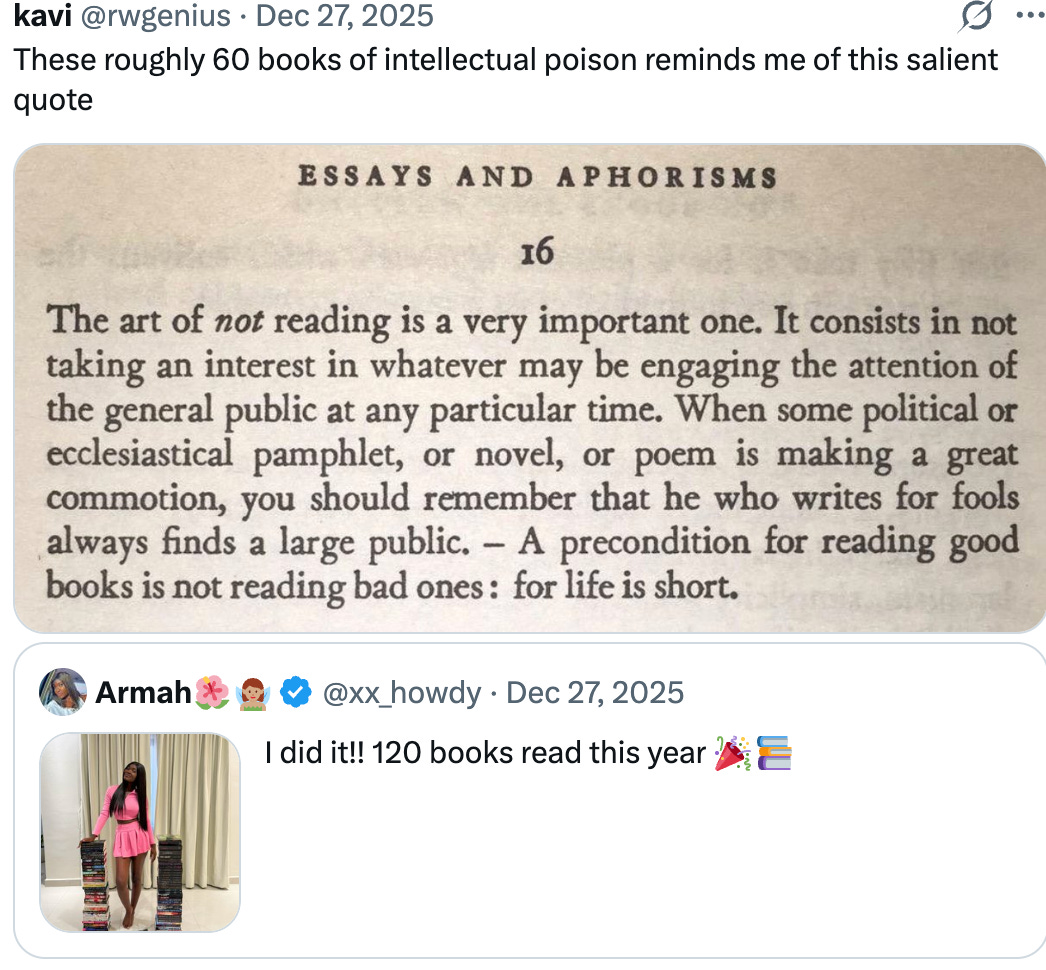

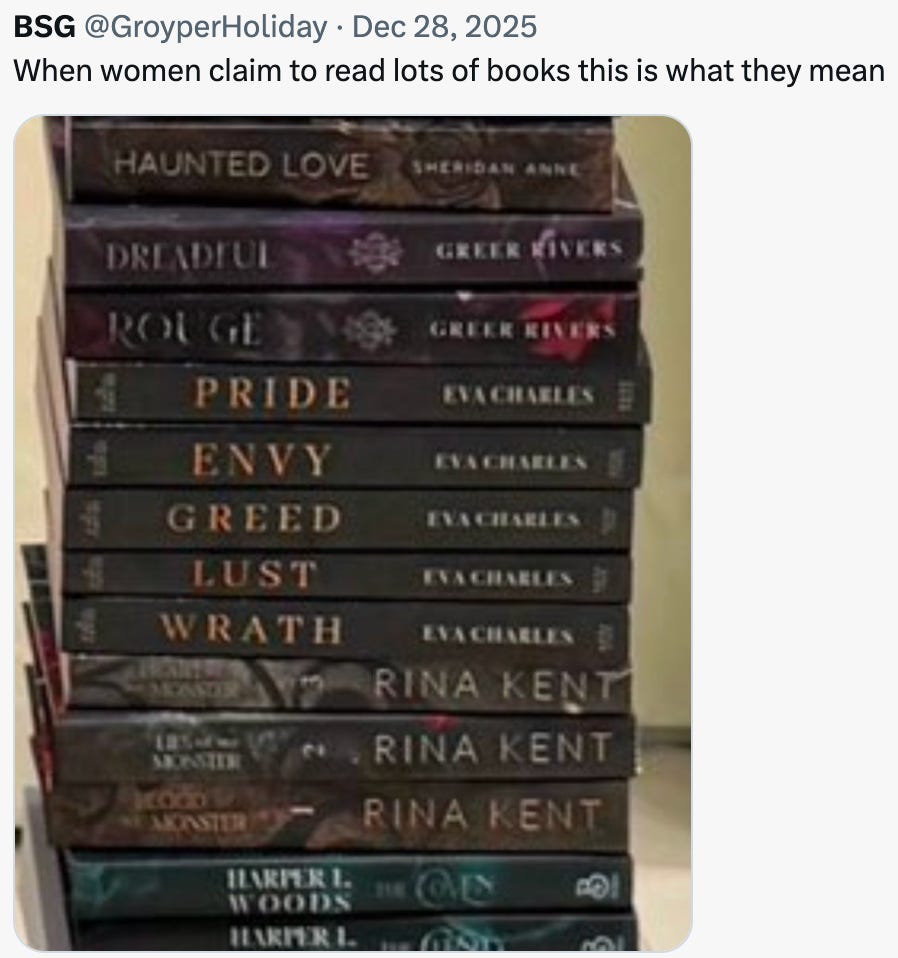

This attitude was exemplified at the end of last year when this young woman posted that she had read 120 books last year.

Armah immediately drew the wrath of the internet. Here she was exemplifying “female misuse of imagination” by posing for an ‘influencer’ style photo wearing clothing that accentuates her shapely figure next to piles of books that are not improving.

This post got 10,000 comments and 15,000 retweets, many with comments, most of them negative. A lot of people seem unreasonably angry with a young woman being proud of having read so many works of light fiction, romantic fiction and erotic fiction. If it were simply that they were not impressed by this accomplishment, why not scroll past? Why the need to criticise her and try to make her feel ashamed of being proud of that? People are forever achieving things we ourselves do not want to achieve, but we do not typically feel the need to tear them down for it. This is clearly not a neutral issue of life goals but a deeply moral issue for many. Why?

The most straightforward explanation is that some of the books are erotic fiction but even there, the moral issue only arises for those who believe that thinking about sex is sinful or otherwise morally wrong. Unlike with filmed pornography, we need have no fears that the characters are performing under coercion or hating their role but have no other way to support themselves financially due to a lack of available work, mental illness or addiction. They are creations of the author’s imagination, shared willingly. The comments on these grounds appear to stem from socially or religiously conservative fears that such imaginings are sinful or corrupting. (Some appear to be by men who enjoy filmed porn wanting to make the point that women like sex too. Yes, we know).

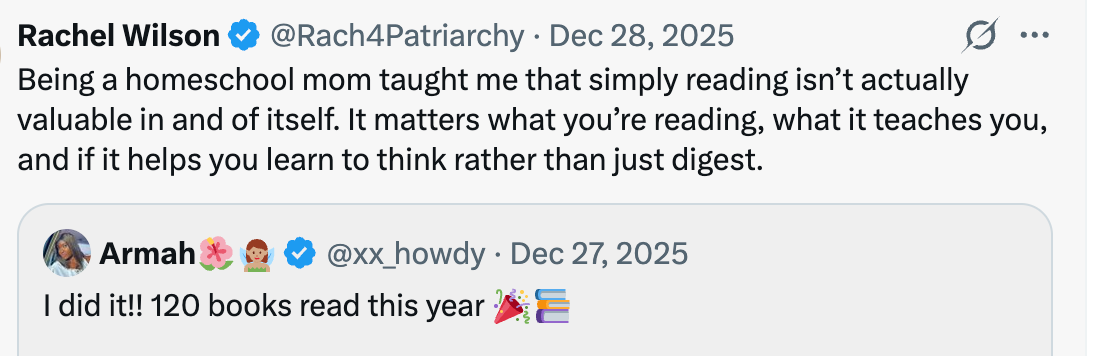

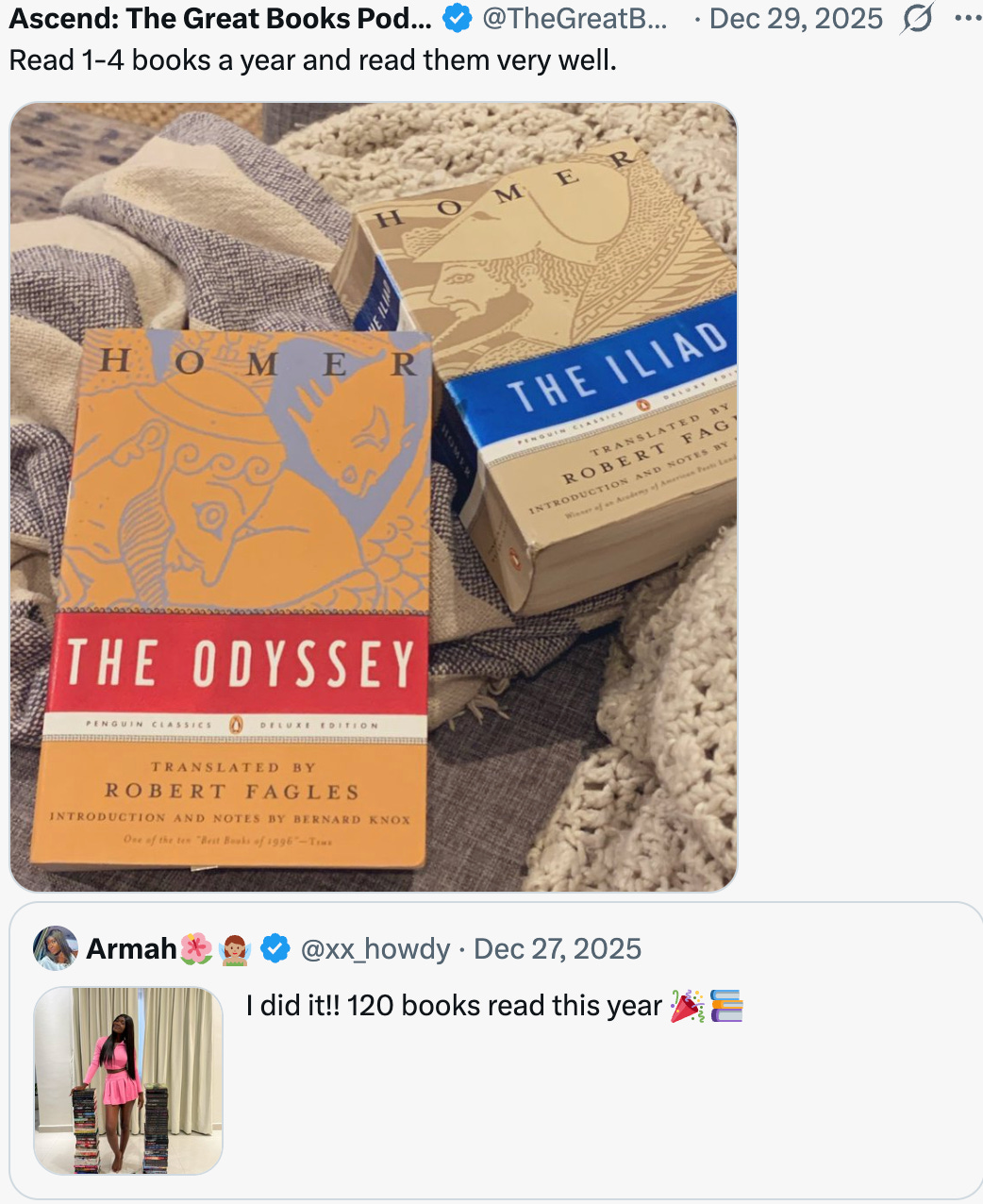

Most comments, however, seem to be angry that Armah is proud of having read books which are not considered of high literary value. People are saying the books were not worth reading and mocking and deriding her for believing having read them to be an accomplishment. The main claim is that she would have done better to read a few ‘good’ books than triple digits worth of crap. This comes from that old, anxious, snobbish divide between ‘improving’ and ‘non-improving’ books and almost certainly from some degree of insecurity.

We live in a society that holds the concept of ‘reading’ in high esteem. It is associated with intelligence, education and seriousness. To be ‘well-read’ is a mark of prestige and, often, of class. There is a perception that for reading to be worthwhile, it must be difficult. It is my observation that this is particularly the case with people who are insecure about how intelligent, educated well-read and serious they are. We see this in some (but certainly not all) the arguments about whether audiobooks ‘count’ as reading or not. This depends on how we understand the concept of a book. Is it the words on the page or the ideas or story conveyed by them? For most people who read easily and effortlessly, it is the latter. Choosing to listen to an audiobook is then typically a way of slowing the process down and enjoying a performance by a skilled voice actor. Alternatively, it can be a way to ‘read’ while walking, driving or doing chores. People for whom reading is still somewhat effortful or for whom reading a book with one’s eyes is actually slower than listening to it are more likely to regard listening to a book as ‘cheating.’

The same is true, in my observation, of people who correct grammar, spelling or punctuation in online social media discussion. These tend to be people who were good at English at school and are proud of that but also regret not having done anything more with this. They wish to demonstrate that they are fully literate rather than discuss ideas. People who write about ideas for a living tend not to worry about this in real time exchanges. Some of the messiest, most ungrammatical and even entirely unpunctuated DMs and emails I receive come from academics and writers. This is a result of thinking faster than one can type and wanting to convey one’s thoughts urgently!

This, then, might explain some of the negative responses. People who find reading difficult or think, for it to be worthwhile, the subject matter should be difficult and are also insecure about this, are indignant that Armah is proud of having read so many books that are not difficult. They themselves would not advertise this and have a desire to present themselves as ‘serious readers.’ If it were simply that their own reading goals were more high-brow and there was no element of status or optics about this, they would simply scroll past, thinking ‘Not my kind of thing.’ They feel angry because of their own fragile self-image. They believe that reading serious and difficult texts gives them a certain status in our culture and that this is undermined by somebody else unapologetically celebrating having read so much lighter fiction!

We do not know specifically why Armah is proud of having read all these books. It is possible but not likely that she is newly literate. My husband is someone who learnt to read as an adult, having been appallingly failed by his school which was then closed down for this reason. In the first year that he accomplished this, he read seven books. They were all Harry Potter. Is this something to be proud of? In this context, absolutely, yes! Anybody criticising him for not having read Homer’s Odyssey would have entirely misunderstood the goal and be very mean-spirited indeed.

It is also unlikely that Armah is proud of having read these books because her intention was to spend the year exploring great works of literature or important philosophical treatises and mistook her selection as fitting these criteria. If it had been, some gentle correction might be in order, but I do not believe anybody thought it was. Her offence was not misunderstanding or misrepresenting quality or seriousness but betraying the fragile hierarchy in which self-improvement must be the goal, difficulty must be performed and enjoyment must be justified. Her offence was reading for pleasure.

Why is this an offence at all? What is the purpose of reading—of fiction, of stories? What value do they have for humans? Humans appear always to have told stories. Our main forms of entertainment involve them, whether in novels, films or video games, and we narrate our own lives and histories in story form.

Evolutionary psychologists have explored this question as part of the human capacity to theorise and think problems through abstractly. Fictional stories present us with hypothetical scenarios and personality types and allow us to consider what we would do in such situations and how we should understand and deal with such people safely while not in immediate danger from them. It is perhaps unsurprising that different genres appeal, on average, to different audiences. Action films, war movies and survival narratives tend to attract more men, while psychological thrillers, romances and reality television have a largely female audience. Ancestrally speaking, male survival often depended on decisive action in high-risk situations, while for women, accurately perceiving social dynamics within a group and exercising good judgement in mate choice and female alliances was particularly important.

Paleoanthropologists have hypothesised from what can be known of other species of human that we are the only one to have had this story-telling capacity and that is what gave us a survival advantage and at least partly explains why we are the only ones left. It is likely that natural selection favoured those humans who enjoyed investing their time and energy in a good story.

Stories can thus be understood as an integral part of our psychological make-up and pressuring people to only read those which are considered to be of high literary merit and potentially difficult or shaming them for not doing so is probably futile. Even if this were possible, it is not at all clear that this is unequivocally good. We humans do actually need downtime and I see no good reason to think that a little healthy escapism into the world of fiction, even if it is not a literary masterpiece, is a detrimental form of relaxation. Despite at least five centuries of alarmists warning that such reading will detach us from reality, foster unrealistic expectations, induce paranoia or ‘distemper’ the mind, and corrupt our manners and morals, there is no convincing evidence that it does so. If anything, social media is a far more plausible culprit.

This is certainly my experience. From 2017 to 2022, I read no fiction at all, having previously enjoyed at least two novels a week. During that period, I believed it essential to devote my reading entirely to postmodern texts and strands of Critical Race Theory, Queer Theory, Postcolonial Theory etc. If anything will distemper the mind, that will. I needed to do this first to write the ‘hoax’ papers, then Cynical Theories, and later to help others understand and address ideological capture in their workplaces. When I was not reading and writing about these theories and their associated activism, I was arguing about them on social media. I eventually suffered a catastrophic nervous breakdown and a stroke-like neurological event that left me entirely out of action for nine months.

During my recovery, I returned first to comforting books I had loved as a child, before moving on to reconsume the complete works of the great philosopher and psychologist, Agatha Christie. I have since indulged my fondness for the peculiarly British genre of the “domestic thriller” (Help! My child has been kidnapped and my husband is about to discover my dark secret. Someone put the kettle on!), at a rate of roughly two a week, interspersed with true crime (because, somehow, reading about psychopathic serial killers is relaxing). I am also fond of semi-fictionalised case studies written by foster parents or special education teachers and have even been known to indulge in the occasional vampire novel (Anne Rice—no sparkling). This has been profoundly beneficial to my mental health and general sense of wellbeing.

I think we should be wary of the kind of snobbery underlain with insecurity that seems to tell so many of us that we all ought to be reading only “improving” books or we are wasting our time and misusing our imaginations. My academic background is in late medieval and early modern English Literature and consequently I have read a great many of the great works, some of them in Latin. I am currently learning to read Old Norse so I can go earlier and get fully into the Poetic Eddas. I certainly do not underestimate the value of great literature and I would love everybody to read more of it. But let’s not allow this to make us underestimate the value of curling up with an easily consumable and satisfying work of contemporary fiction or to feel shame about enjoying these and that we ought to be doing something more worthwhile and challenging.

Stories are what we humans do. There are good reasons that we do this and we enjoy doing it. A fiction book can best be understood as one human saying “I imagined this scenario and these people and I wrote it down. Would you like to imagine them too?” Other humans can then read the blurb and decide that, yes, this does look like a pleasant way to spend a couple of evenings or, alternatively, that, no, this particular imagining is not for me. It really does not need to be more complicated than that.

Many props to your husband for learning to read as an adult

So true, Helen.

Stories connect us to one another, to different vantage points that enable insight into our shared human condition, and to ourselves.

And sometimes what the mind and “soul” require is a bit of “fluff”, or any other oft-derided form of reading, rather than a deep academic experience — just look at the pair reading together on the cover of “Frog and Toad Are Friends” 😻