Liberalism as a Higher-Order Value

A response to reader comments

(Audio version here)

In a recent piece on whether the terms ‘far-left’ and ‘far-right’ mean anything anymore, I argued that a stance can be coherently and measurably recognised as ‘far’ - extreme, radical - when it is unambiguously illiberal. That is, when it denies the fundamental principles underlying liberal democracy - individual liberty (individualism), viewpoint diversity (pluralism) and universal rights and responsibilities and democratic processes (universalism). This provoked a lot of (mostly positive) discussion, and two comments stand out.

Connie, a relatively new contributor to our discussions with an academic background in philosophy, writes,

It’s been bothering me for a while that I keep getting nudged back and forth on the left-right political spectrum, while my general political perspective has pretty much remained the same over the years. Today I’m questioning whether it should even be a spectrum with a “center”.

Helen’s walk-through of the diverse real-life manifestations of left and right is a good argument for changing the whole framework. I’ve long thought that Libertarianism belongs on some kind of narrow orthogonal offshoot from the spectrum. Perhaps “conservative” and “progressive” need a different kind of framework than a two-dimensional line.

There is, of course, the very useful “Political Compass” test which plots people on a graph that measures both their left-wing and right-wing views and their authoritarian or libertarian values.

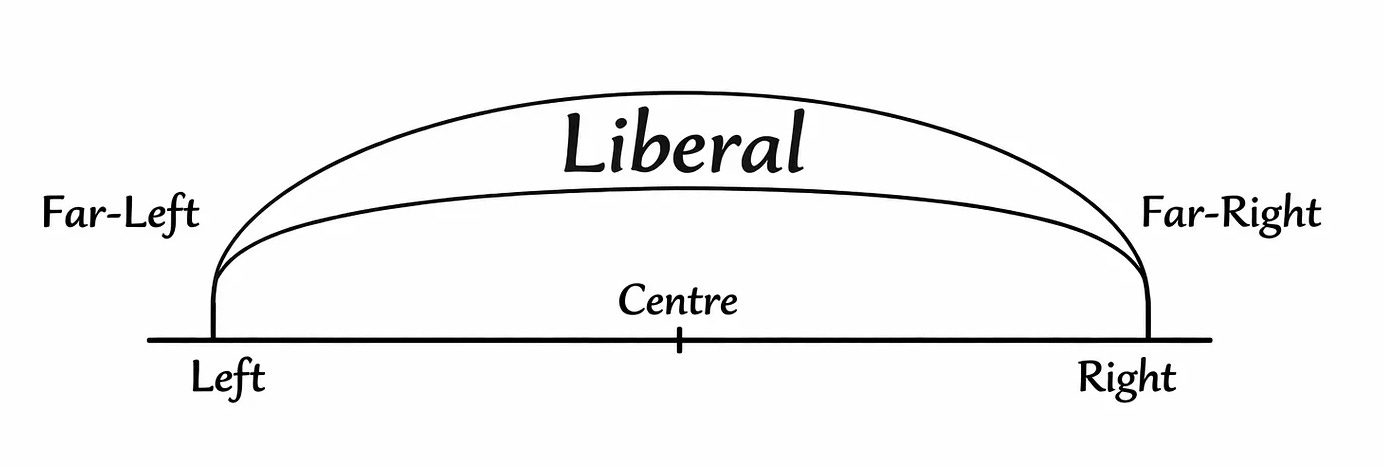

I see things a bit differently, however. I see liberalism less an axis different but equivalent to the left/right one and more as a higher-order value. This is because liberalism is the precondition for productive political disagreement. Because Western liberal democracies are founded on liberal principles as a governing system and (ideally) a set of well-established cultural norms and expectations, this provides the core basis for our kind of democratic societies that protect individual liberty and facilitate the free exchange of diverse viewpoints for the purposes of knowledge production and conflict resolution. It can be imagined as an umbrella that covers the majority of mainstream political thought as a default. Those extreme views on the fringes of either side which would curtail individual liberty, suppress viewpoint diversity and interfere with democratic processes and/or the constitutions of countries established to protect individual liberty and government by the consent of the governed are the views I have argued can coherently be considered extreme, radical or far. These are revolutionary or reactionary views which seek to dismantle the liberal, philosophical underpinnings of Western modernity and replace them with some Utopian vision of progress or a regression back to an imagined golden time of patriarchy, racial and religious homogeneity and persecution of sexual minorities.

If we imagine an well-functioning liberal society in which the vast majority of people on both the left and the right strongly support individual liberty, viewpoint diversity and value our shared humanity and the radical views which do not are marginalised to the fringes, it would look something like this:

(N.B. This does not mean that liberalism is the same thing as ‘centrism’ but that when a society is overwhelmingly liberal, liberal principles are organically at its centre. We can imagine a society in which the mainstream conservative views are illiberal - perhaps an Islamic theocracy - and the progressive stance opposes this and then the liberal umbrella would cover much of the progressive side of the spectrum and very little of the conservative side. Likewise, in a society where the mainstream left-wing views were illiberal - maybe a Marxist state - and those on the right are in opposition to that, the liberal umbrella would cover most of the right-wing spectrum and very little of the left).

I expressed this to Connie like this,

I’m inclined to think of liberalism as a “higher order” value that covers the things we must preserve before we can meaningfully have political sides that can engage in the tug of war over progressive or conservative policies, large government or small, taxes, housing, welfare programmes, international relations etc. If we don’t have a society that protects individual liberty & democratic processes and facilitates the free exchange of diverse viewpoints effectively to advance knowledge and resolve conflict, the people who make all those decisions will ultimately be whichever authoritarian faction is able to gain power. This is why I think it is in the interests of everyone to defend liberalism.

One of our regular thoughtful commenters, Neil, then responded,

Defined as a higher order value, then, Helen, you’d define liberalism as “protects individual liberty & democratic processes and facilitates the free exchange of diverse viewpoints effectively to advance knowledge and resolve conflict”?

Whilst I’d agree, the counter point is that our current ‘next level down’ political parties would all be likely to claim these are already part of their core values?

Yes! Exactly! This is precisely what we want and we need to focus on this specifically and hold political parties to it. We need our political leaders to affirm these core values very explicitly to preserve the functioning of our liberal democracies. By keeping the core liberal principles front and centre as well as left-wing or right-wing policy positions, liberal leftists and liberal conservatives can consistently hold their political leaders accountable for upholding these and have a measure by which to marginalise their illiberal extremists through internal critique. As we get increasingly politically polarised on right-wing or left-wing party politics, it is easy to let slide the fundamental liberal principles that all inhabitants of liberal democracies should be invested in maintaining.

The fact that political parties in power claim to uphold liberal values even while failing to live up to them in many ways in practice is precisely why liberals need to be vigilant and consistently principled, but it does give us a solid basis to work with. We frequently fail to do so because we get so distracted by the (important) specific policy decisions at hand that we miss the bigger picture, which is the foundations of liberal democracies themselves.

When Keir Starmer was confronted by an elected MP asserting that it should be made illegal to desecrate holy texts and insult prophets and he prevaricated on this by saying that the government was committed to tackling all forms of hatred, the political right noticed the failure to uphold freedom of belief and speech but the discourse on left was dominated by discussion of anti-Muslim bigotry and immigration. We needed liberals from both sides to say, “No, Prime Minister, the correct and immediate response to that should have been “Sorry, Mr. Ali, but no. While criticism or mockery of religion can be experienced as hurtful by believers, we must protect the right to do so in a liberal society.” When Donald Trump threatened to remove the licences of TV stations that are consistently critical of the Republican Party and his administration, the left pointed out the threat to freedom of belief and speech but discourse on the right was dominated by discussion of the bias of the channels in question and whether this was just revenge for left-wing censorship. The liberal response to that from both sides needed to be, “No, Mr. President. I’m sure you meant to say, “I don’t like those channels but I will defend their right to exist and criticise the government in the spirit of the constitution of our great country. I encourage everybody to consume a variety of news sources.”

Political leaders frequently express their commitment to liberal values while betraying them. Paradoxically, perhaps, the continued expression of those values is a good sign! Political leaders clearly believe that the people still expect this of them. Our aim must be to show them that they are correct about that and do so particularly with our own parties. We must also be prepared to do this with the members and supporters of our own side. We get the political leaders we ask for and so it matters that the prominent and mainstream voices on each side uphold those foundational liberal principles, and illiberal extremists are recognised as such and relegated to the fringes. They still have a voice and can contribute to the conversation but the commitment to liberal democracy holds.

The strongest critics of liberalism on the left are the Marxists and the Critical Social Justice (woke) movement. Contrary to narratives on the right (and occasionally on the left), these are not the same thing. Marxist critiques of liberalism have (since Marx) been economic. They are materialists who believe in objective truth and the importance of dialectic, but have a radical and single-minded focus on the source of societal injustice. Marxists object to capitalism which is a central pillar of liberalism and read everything through a class-based lens that holds that the wealthy use capitalist systems to consolidate power in their own hands and exploit the working class. They typically reject identity politics as dividing the working class and distracting from a focus on economic systems.

The Critical Social Justice (woke) movement is very much embedded within capitalist & corporatist systems but may pay lip-service to anti-capitalist rhetoric. They oppose liberalism on epistemic and moral grounds, taking the postmodern stance that rejects the concept of objective knowledge and the later evolution of that which holds that identity politics are required to achieve social justice. “Critique of liberalism” is a central tenet of Critical Race Theory and also features heavily in Queer Theory, Postcolonial Theory, Intersectional Feminism and Dis/ability studies. Activists typically believe that individualism and universalism are White, Western, masculine concepts that perpetuate oppression.

Both of these radical factions embrace collectivism and reject the concept of individual liberty where it contradicts their own ideology. Contemporary Marxists are generally more open to engaging with diverse viewpoints while ‘wokeists’ believe that social justice can only be achieved by censoring ‘dominant discourses’ (common ways of talking about things) seen as perpetuating oppression and instilling their own into everybody. Their attitudes towards democratic processes and constitutional procedures are variable and complicated. In the case of the CSJ movement, they are often incoherent. It is the ‘woke’ who have presented most direct illiberalism by gaining power and prestige both within institutions and culturally via mainstream media and social media, resulting in the Cancel Culture which hit a peak in 2020 and has been waning ever since but has not died.

Liberals on the left need to engage with both groups, but we must not be distracted from their illiberalism either by our sympathy for some of their aims or by a conviction that the illiberalism on the right is worse and so we need to maintain solidarity and not “punch left.” Marxists make some good critiques of some aspects of capitalism and of class power and of the ‘woke’ that we should take seriously. The Critical Social Justice movement is not wrong that cultural discourses have power and biases that affect marginalised people exist, and we share their opposition to racism, sexism, homophobia etc. We can incorporate any insights they might have without giving any quarter to illiberal methods - censorship, collectivist moral coercion, inconsistent principles, rejection of universalism and equality under the law etc. The illiberal elements on the left - overwhelmingly the woke - continue to have power and influence because the liberal left failed to push them back. Political leaders adopted their illiberal stances and rhetoric because the demand for it was so loud and equally vocal internal critique was lacking. We must change that ratio.

The strongest critics of liberalism on the right are the post-liberals, the reactionary and far-right and the post-truth identitarian populist right. It is more difficult to pin these right-wing currents down precisely in this piece because they vary from country to country to a greater extent than Marxists and the ‘woke’ do. Conservatism always varies culturally because conservatives are seeking to conserve different cultural norms and traditions and this remains the case with the far-right. The illiberal right in the UK has decidedly different features to the illiberal right in the US, for example. Nevertheless, we can distinguish three distinct dominant currents.

The “post-liberals” are a mixed bag (and this tems can also be argued to describe some currents on the left). Many on the right root their values in religion while others focus more on cultural tradition and imagined homogeneity (a particularly prominent difference between the US and UK). Some overlap strongly with what is often referred to as ‘paleoconservatism’ while others still operate within largely liberal conservative assumptions and some are radical revolutionaries. What they have in common is a perception of moral emptiness, social fragmentation or excessive individualism and a drive to regain a sense of community, authority, a common good and shared values. They conclude that liberalism has failed and needs to be replaced, but may be vague about what that replacement will look like in practice. They are characterised by dissatisfaction and often a kind of nostalgic longing.

The far-right, reactionaries, Christian Nationalists and/or ethnonationalists are much the same as they have always been. These are the movements that are overtly illiberal and rather than believing liberalism to have failed, were always fundamentally opposed to it. They are overtly hierarchical in a way that is not compatible with liberal democracy, hostile to pluralism and viewpoint diversity and unapologetic about restricting individual liberty. They endorse all or some mix of ethnonationalism, racial or religious supremacy, a patriarchal social order and the persecution of sexual minorities.

The post-truth, identitarian populists are the most prominent and politically powerful illiberal group on the right and they are worrying (and distinguished from broader populist movements) because they draw on both other groups and overlap with them, calling on the disillusioned, nostalgic myth-making that appeals to the post-liberals and the identitarian illiberalism that appeals to the far-right. The post-truth, identitarian right mirrors the epistemology of the postmodern left in favouring ideological narratives over objective truth, largely disregarding any need for evidenced and reasoned argument and using identity politics and “lived experience” arguments and engaging in moral relativism and motivated reasoning. This is a direct rejection of the epistemic underpinnings of liberalism which values pluralism, viewpoint diversity and the free exchange of ideas as a way to advance truth and thus presupposes that objective truth exists and can be obtained via reasoned and evidenced argument.

Liberals on the right need to engage with all these groups. They too will need to be careful not to be distracted from the illiberalism on the right by sympathy with some of their legitimately conservative aims and resentment at the illiberalism on the left and a feeling of needing to give them a ‘taste of their own medicine.’ Some conservatives have been expressing the view that the right needs to maintain solidarity to see out the excesses of ‘wokeness’ and urging others to see ‘no enemies on the right.’ This is the same mistake as that made by liberal lefties that allowed the CSJ movement to gain dominance in the first place. It is vital that liberal conservatives vocally oppose those on their own side who are hostile to liberty, seek to suppress dissent, reject the concept of truth-seeking and demonstrate contempt for democratic constraint. If we lose the liberal principles that define Western liberal democracies, it will be unclear what, if anything, traditional conservatives are seeking to conserve.

In the case of far-right reactionaries, this engagement must be strong critique that shows their stance to be thoroughly illiberal and enables it to discredit itself and be marginalised from the range of conservative thought considered worthy of respect.

Conservatives who wish to conserve liberal democracy need to engage seriously with the dissatisfaction and nostalgia of the post-liberals, some of whose critiques are serious and historically informed and convince them that a rejection of liberal foundations risks repeating pre-liberal errors. There is no time in which a society of humans has been ideologically homogenous and held to a shared sense of the ‘common good.’ Instead they have factionalised and factions have fought to assert their own value system and impose it on everybody else before being knocked bloodily aside by another. It is the liberal principle of freedom of belief and speech that enables people to live according to their own beliefs within their own religious or moral communities.

They must engage too with the post-truth, identitarian populist right and be seen to argue visibly and well for the importance of understanding ‘truth’ as ‘that which corresponds with reality’ and reality being best established by evidence and reasoned argument rather than by what conforms with ideological narratives. Liberal conservatives need to assert traditional conservative values that have always included holding consistent, reasoned principles and incremental reform and valuing individual responsibility, self-restraint and civility. This is a philosophical tradition that has no room for base collectivist identitarianism and crass and vulgar showmanship, anti-intellectualism and “strongman” posturing. If right-wing illiberalism is not visibly pushed back by ethical conservatives, illiberal political leaders will only be further emboldened to believe they are meeting a demand and become more illiberal and continue to undermine the liberal foundations of the Western Civilisations that conservatives typically seek to conserve.

To achieve all of this, it is essential that liberals on the left and the right hold their liberal principles at the forefront of their minds while discussing the goals, aims, values and policy decisions of political parties and leaders. We must also do so when addressing the public political discourse generally and the various illiberal factions that have influence, especially on social media. It is not sufficient to do this only when illiberalism is evident on the other side. It is essential to accurately critique our political opponents but this can be easily dismissed as political partisanship even when it is not. We are most effective when we address illiberalism on our own sides and doing so honestly and consistently also enables us to work cooperatively and respectfully with liberals across the political spectrum. Only ever criticising one’s political opponents increases polarisation and enables radical and extreme views to thrive. Criticising one’s own illiberals and extremists recentres mainstream political discourse within reasonable, ethical and liberal bounds and decreases polarisation.

It is in this way that liberalism is best understood as a higher-order value - a precondition for societies in which productive and ethical political disagreement can flourish. To preserve our liberal democracies, we must preserve the epistemic foundations of liberalism which hold that objective truth is obtainable and the best way to access it is via evidenced and reasoned arguments between people who disagree and whose right to disagree is defended by strong protections for freedom of belief and speech.

Illiberal tactics can appear effective in the short term to achieve specific political goals — ban these ideas, deny that freedom, discriminate against this group — but once established and normalised, they are highly prone to being turned against those who first advocated for them when public tolerance for the authoritarianism runs out and power changes sides. It is therefore in everyone’s interest to resist the erosion of liberal norms wherever it occurs. This is true for progressives who want to achieve lasting progress, and for conservatives who wish to conserve anything worth conserving at all. Liberalism, therefore, should be regarded not as one value among many, but as the higher-order value that allows people with deeply different political values to disagree productively and resolve conflict without coercion or force.

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has over 6000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.8% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2026 is to increase that to 7%. This would enable me to write full-time for my own substack! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

Great piece here, Helen, especially the dimensional clarity you provide in seeing how Liberalism spans the spectrum of Conservative <-> Progressive, yet sits above them as its own higher order set of values, virtues, and vision.

While there may not be much "common ground" in the particulars of all the various movements and moods afoot these days, your framing of Liberalism here offers a "higher ground" place where there is perhaps more "solid ground" to build a sustainable future for those interested and able to do so.

Delighted to trigger ideas in someone who thinks and writes much better than I do. This is one of my reasons for commenting and occasionally posting on Substack.