Reform Is Not Genocide

Liberalism, Islam, and the difference between opposing ideas and harming people

(Audio version here)

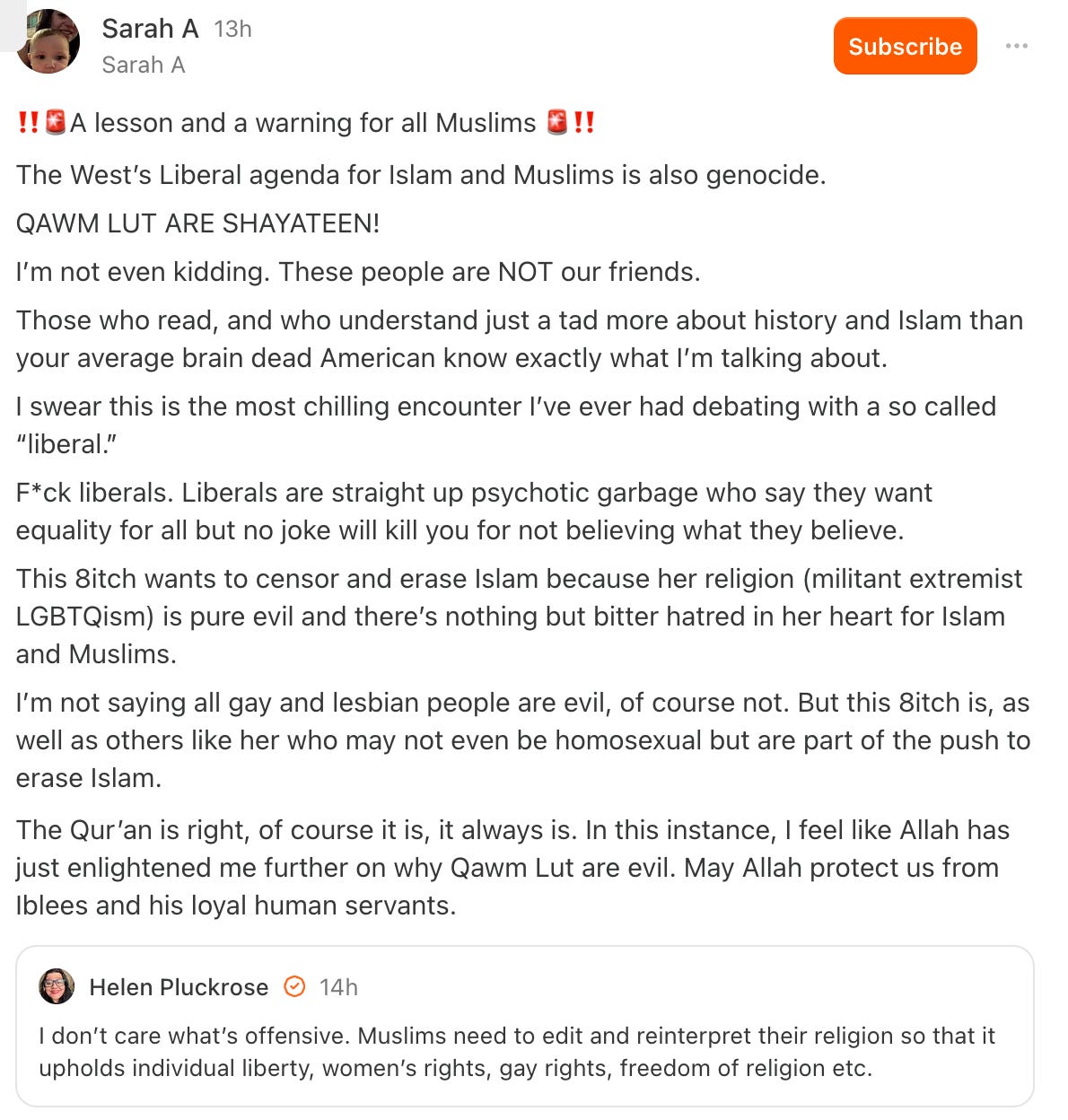

In the comments on my recent piece on Islam, I found myself in a protracted exchange with a Muslim commenter named Sarah. I had argued that liberal Muslims need to intervene more assertively against authoritarian interpretations of their faith, and that the mainstream practice of Islam must be reformed through persuasion and internal critique to support individual liberty, women’s rights, gay rights, and freedom of conscience, including the freedom to criticise religion.

In response, Sarah accused me of wanting to “genocide Muslims.”

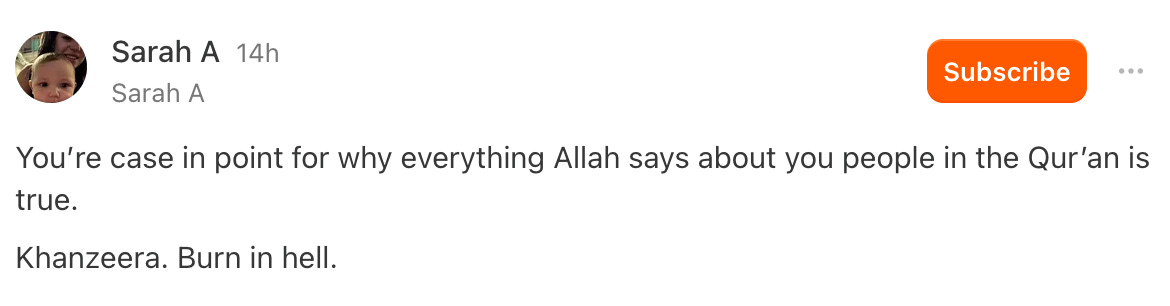

She did not mean this metaphorically. As the screenshots below show, she described liberalism itself as genocidal, characterised liberals as enemies of Islam, and framed my position as an attempt to erase Muslims altogether.

At first glance, this reaction seems so disproportionate that it tempts one to treat it as mere hysteria or bad faith. But doing so would miss something important. Sarah’s response is not an aberration. It is the predictable result of both a zealous commitment to a belief system held to be perfect, final and divine and a deep and widespread confusion about what liberalism is.

One thoughtful commenter intervened to resolve the stalemate, saying:

I think the situation being described may be explained like this. If only Catholics were more…..Protestant. It seems Sarah is saying if the liberalism you propose is implemented, then the result is a different religion and no longer Islam.

Yes. Exactly. Sarah would be correct. If the liberal reforms I argue for were fully implemented, the result would indeed be a radically transformed version of Islam that some would argue was no longer Islam at all. The odd thing is not this conclusion, but the persistent assumption that I might somehow be unaware of it.

I am fully aware. It is the point.

I have spent much of my adult life arguing for liberalism, for the marketplace of ideas, for the claim that some ideas are better than others, and that bad ideas can and should lose out to better ones through open criticism, argument, and evidence. The ideas I advocate are consistently liberal ones. This should make it obvious that I am consciously arguing for people to abandon illiberal beliefs and adopt liberal ones. This is not an accidental side-effect of some other project. It is the project.

Confusion about this only seems to happen to liberals. I doubt very much that, when Sarah advocates that everyone ‘revert’ to Islam (as she will if she follows her faith in the customary way), many people assume she has realised that if people actually do this, the result will be that they have different beliefs to the ones they held previously. They will recognise that this is precisely what she wants and understand that it is because she thinks the beliefs they held previously were wrong and Islam is right.

The same is true in politics. When someone campaigns for a political party, they are explicitly trying to persuade others to vote differently than they previously intended. No one objects, “But if you succeed, they will no longer be voting Labour and their political orientation will have changed.” Yes. That is the entire purpose of persuasion.

Yet liberals are repeatedly treated as though they have failed to notice that advocating liberalism entails wanting people to become more liberal and to stop believing and doing illiberal things. Why?

I think there are two related confusions at work.

The first is a failure to distinguish between respect for freedom of belief and respect for all beliefs. Liberalism requires the former, not the latter. Respecting someone’s right to believe something does not entail believing that their beliefs are good, true, or harmless. That position is not liberalism but relativism.

Built into the foundations of liberal philosophy is the position that some ideas really are better than others and that protecting freedom of belief and expression is the best way to allow better ideas to be tested, criticised, refined, and ultimately to prevail. It is therefore entirely compatible with liberalism to argue that certain ideas are bad and should disappear. This is precisely how many deeply harmful ideas like slavery, child labour, racial hierarchy and the legal subordination of women have already been marginalised. They became morally untenable through liberal critique. Illiberal interpretations of religion are no exception.

Far from threatening religious believers, this process protects their right to defend their faith, respond to criticism and misunderstanding of it, increase confidence in it and allow it to prevail. As John Stuart Mill wrote in On Liberty,

[T]he peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

The second confusion is related to this because it comes from a conflation of believing that certain ideas are bad with believing that they should be banned or suppressed by force. Because banning ideas is incompatible with liberalism, some people think that a liberal may not fully appreciate that they are saying a certain set of ideas is bad and should die. This is simply incorrect. As indicated above, a liberal is someone who holds two positions in their head at the same time:

These ideas are bad.

People must be free to hold and express them.

I think this is genuinely counterintuitive to many, if not most, people and this is why the confusion exists. The assumption is that if you think an idea is dangerous, the intention to suppress it by force follows naturally. When a liberal explicitly rejects such force, critics conclude either that the liberal does not really believe the idea is dangerous, or that the liberal must be lying and harbour authoritarian intentions.

I think this is precisely what happened in my exchange with Sarah. She does not believe Islam can be liberal and still be Islam. She correctly recognises that I want illiberal interpretations of Islam to cease to exist (because I want illiberalism to cease to exist). But she draws the wrong conclusion from this.

Instead of understanding that I want people either not to be Muslim at all (this is ideal because I do not believe the religion to be true) or, failing that, to interpret their faith in ways that uphold the rights and freedoms of others, she concludes that I want to end the existence of human beings who are Muslim.

This is a category error.

I wish to see an end to illiberalism among Muslims in exactly the same way I wish to see an end to it from every other quarter in which it materialises, but Sarah sees the illiberalism I describe as integral to Islam and responds with visceral rage and an accusation of genocidal intent. She probably does not do this consistently.

If Sarah holds orthodox Muslim beliefs, she will wish everyone to become Muslim every bit as much as I wish everyone to become liberal. She will likely understand her own aim not as a desire to genocide non-Muslims, but as a desire for people to abandon false and harmful beliefs in favour of true and beneficial ones. That is exactly how I understand my own position.

The difference is that liberalism allows me to recognise this symmetry. I can cognitively grasp Sarah’s goals, defend her right to hold them, and support her freedom to argue for them so long as she does not seek to impose them by force, harm others with them or deny them the same freedom.

Whether Sarah can return that favour is far less clear. On the evidence I have so far, I am not optimistic. That, ultimately, is what makes belief systems that regard themselves as perfect, final, and divinely authored so troubling. It is less that they exist and seek to persuade others of their rightness but that they so often cannot tolerate the existence of contrary views, distinguish criticism of ideas from violence against people or see such criticisms as anything other than an insupportable insult and an existential threat.

This is a dangerous mentality.

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has nearly 6000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.4% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2025 is to increase that to 7%. This will enable me to keep doing this full-time into 2026! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

Thank you. This is expressed so clearly. I am both a Christian and a liberal. I do believe my faith is a positive good and better than other belief systems, and also respect the rights of others to disagree with this assertion.

Sarah and trans activists seem to be drawing from the same playbook: my refusal to accept their beliefs gets reinterpreted as genocide.

I had a student in class say: “I am ok with people identifying as they please, but not ok with being forced to affirm their beliefs.” I thought this was a a nuanced and tolerant position for a young Christian male college student to embrace — and brave of him for uttering it. Unfortunately, a trans student stormed out of class in tears and one of his friends complained to me about how intolerant these “Christian types” are. The next day, said trans student came to my office to complained that I had not shown care for his feeling in the current “genocidal” environment we are leaving under in the US 🤡🤡