Strategically Shunned or Just Intolerable?

How to tell the difference between being shunned for your politics and being avoided for your personality

(Audio version here)

The New York Times recently published a piece: “Is It Time to Stop Snubbing Your Right-Wing Family?” In it, the author, Tim Enthoven, discusses his previous policy of rudeness/frostiness/unfriendliness to his brother-in-law. Enthoven describes feeling that it was both his ‘civic duty’ and ‘strategic’ to shun those who do things like support Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill and stance on immigration, approve Robert. F. Kennedy’s MAHA mandates and watch Joe Rogan. “How else could we motivate them to change their ways?” Enthoven has now changed his stance on this both because he believes that it will not change anybody’s mind and can only drive more division and polarisation and because he was denying himself the friendship of his brother-in-law which, having allowed himself to experience, he very much values as a generous and supportive one.

The comments on this piece are dominated by left-wingers answering the question of whether one should stop snubbing one’s right-wing family with a resounding ‘No.” It is these comments more than the piece itself to which people on social media have been drawing attention. They are cited as evidence that the problem of intolerance and polarisation is coming from the left. There is certainly truth in this. The highly self-righteous, moralistic and articulated justifications for shunning are clearly more prevalent on the left. Whether this means the right is more tolerant of left-wing views generally or whether it expresses intolerance differently is debatable. There has certainly been a great deal of right-wing populist rhetoric claiming that ‘the left’ whether conceived as communism or “woke” or sometimes, confusingly, both, presents an existential threat to Western Civilisation. Nevertheless, the accusation that it is elements of the left who are particularly prone to cutting off friends and family members on the grounds of political differences is justified, and often openly embraced by those elements.

Is this necessarily a moral failing? Is it hypocritical for progressives who champion tolerance and advocate for diversity and inclusion to decline to be at all tolerant or inclusive of diverse political viewpoints? I have long argued that it is and appealed to fellow leftists to recognise that progress is made by enabling and encouraging the free exchange of as wide a range of ideas as possible and engaging in robust but civil debate about them. This becomes very difficult when people taking one side of a debate simply will not talk to the people on the other, and the left has been particularly guilty of this in recent years.

Nevertheless, when it comes to personal relationships - friendships or family ties - I have some unease with the assumption that it is inherently bad to sever them due to a difference of ideas or values. This not only seems to raise an issue for the liberal principle of freedom of association which affirms the right to choose and to refuse personal connections, but on a deeper and more individual level, to misunderstand the fundamentally personal nature of human relationships. It is not only normal but healthy to form those based on shared values and genuine respect and liking for the other person. Staying in relationships where these elements are lacking can lead to unhealthy dynamics of insincerity, codependence, or even abuse.

For some relationships, unconditional love can, of course, be healthy or just unavoidable, particularly in the case of children. With most human relationships, however, love, liking and/or regard is not unconditional. Nor should it be. If my husband changed his values to ones I found morally abhorrent and stopped being a man I could love or respect, our relationship would ultimately have to end unless he remedied this. If other family members or friends stop being people whom I can like and respect and I begin to strongly dislike being in their company, I am under no obligation to pretend this not to be the case and continue to endure close connections with them (assuming they are not having an acute psychological crisis). Enthoven gets at an important distinction when he writes,

No one is required to spend time with people he or she doesn’t care for. But those of us who feel an obligation to shun strategically need to ask: What has all this banishing accomplished? It’s not just ineffective. It’s counterproductive.

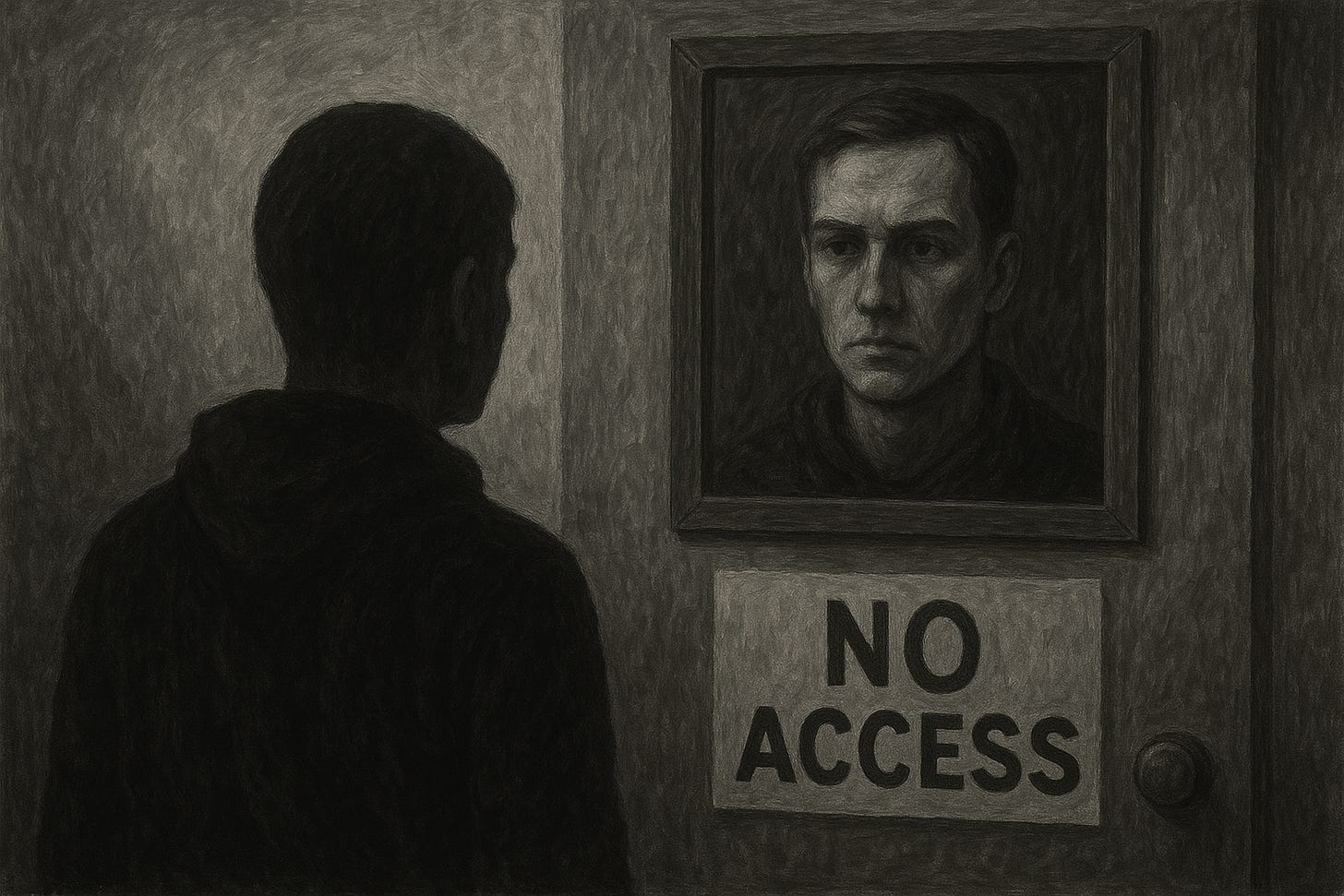

This is a key distinction. It is one thing when a family member or friend changes their values so profoundly that they seem like a different person whom one cannot like, respect or wish to spend time with. It is another when that person still is, in all other respects, somebody one does like and respect and enjoy spending time with but whom one feels one should shun for their politics with the aim of getting them to change their stance. The former is part of the organic process of human relationships. We are psychologically complex animals for whom making and sustaining bonds has a great deal to do with how psychologically compatible we are. Because of that, people often come and go from our lives quite naturally as people change. The latter is a form of political activism that interferes with making or sustaining healthy human bonds and should be recognised and interrogated honestly for what it is.

Is there always a clear line here, though? I think there usually is, but it requires self-awareness and honest introspection as well as being able to separate the personal from the political.

The close relationships we choose for ourselves tend to be based on shared values and compatible traits. We pick people whose good points are the ones that matter to us most and whose faults are not deal-breakers. We do not choose our family members, but if they lack the qualities we value most, or possess too many of the traits we find hardest to tolerate, it is unlikely the relationship will be close. This ultimately comes down to virtues which are rooted in values. Virtues/values can be things like ‘honesty,’ ‘loyalty,’ ‘compassion,’ ‘generosity,’ ‘a sense of fairness.’

Virtues and values are not the same as politics, though they often overlap at the level of principle, and in how those principles manifest in the world. However, when we think of the reasons we like and respect someone, we tend to think of their virtues and values and think of this as their personality or their character which is ultimately about their psychology. These are the aspects of that person that really are individual and personal to them and manifest in relational ways in their personal relationships with other individuals.

However, while personality traits influence principles, and those principles can map differently onto political ideologies, it would clearly be nonsense to assume that someone's politics tells you everything important about their character. People with opposing political beliefs can share the same core virtues and people with shared political labels can differ wildly in their personality/ psychology/virtues/values. It is therefore entirely possible to like and respect somebody as a person even if one has different politics and/or votes differently. It is also possible to intensely dislike and have no respect for somebody who shares one’s own political aims entirely.

I find that I cannot genuinely like or respect people who:

Do not care about what is true. (Evidence-based epistemology)

Wish to restrict anybody’s freedom to believe, speak, live as they see fit even though it harms nobody else nor denies them the same freedoms. (Individual autonomy)

Are hostile towards any group of people defined by innate characteristics or a group identity about which negative generalisations will always be untrue of many. (Universality, common humanity)

People who are cruel and engage in malicious, bullying behaviours and find glee in the downfall of others, even if they are political enemies. (Charity, empathy)

Dispositionally, I clearly have psychological traits which fit me to the philosophical stances known as “empiricist”, “liberal” and “humanist” and this can be distilled into the principles (in parentheses) that will influence my engagement with politics. But does this automatically place me on the left or right of the political spectrum? Not necessarily. I position myself on the left and am a member of the British Labour Party because I endorse policies that support progressive taxes, workers’ rights, affordable housing, national healthcare, a strong welfare system and other traditionally left-wing, class-orientated interests. Nevertheless, the people I like, love & respect include conservatives who differ with me on matters of policy but share my core values listed above. This includes my lifelong Tory voting father who grumbled that I was a “radical socialist” (no) and “bleeding heart liberal” (well, maybe), but liked, loved and respected me right back. While many of the intellectuals and commentators I most admire may share my political leanings, my personal relationships with others are shaped less by what they believe, but by how they believe it, why they believe it, and how they treat others, including those they disagree with.

Imagine two men called Joe and John. They describe themselves as conservative Christians. I am a left-wing atheist. Joe is a Christian because he believes Christianity is true and being Christ-like is the way to live. He does not want anybody to be forced to share his faith, he believes all humans are neighbours he must love and his mode of engagement is compassionate. John has taken on Christianity superficially as a nationalist identity and he has done so in an authoritarian way that he uses to justify his racist, misogynistic, homophobic abuse of others. If I deeply value my friendship with Joe but want nothing to do with John, even if he is my father or brother, or even if we were friends before he took on a Christian Nationalist stance, does that make me an intolerant leftist who shuns people simply for being Christian conservatives? Clearly not.

This distinction applies broadly and includes people whose political end-goals I broadly share. If I cannot like or respect a ‘woke’ leftist who evaluates people’s worth by their skin colour, is cruel and abusive to those they disagree with and wishes to no-platform gender critical feminists and cancel people who inadvertently used a term that is now considered racist, this does not indicate an intolerance of progressives or ‘the left.’ This isn’t strategic shunning; I’ll happily engage any of them in civil, good-faith debate. I simply don’t choose to form close relationships with abusive, authoritarian collectivists, regardless of their politics.

This distinction between “People who hold political stances with which I do not agree” and “People who exhibit personality traits, values and behaviours I find deeply unpleasant and morally abhorrent” is very important. If you are a liberal and think viewpoint diversity is important, consider your own social circle and the people you like and respect. Does it include people who could be described as ‘left-wing’, ‘right-wing,’‘liberal’, ‘conservative’ ‘libertarian’ and a range of variations on these and other political stances? If so, this is a good sign that you are not strategically shunning people who do not share your politics and genuinely are keeping yourself open to engaging with different viewpoints. Is your social circle devoid of people who could be described as ‘authoritarians,’ ‘abusive tribalists’ and “dishonest bullies?” This is also a good sign. It indicates that you are someone who will not tolerate such behaviours even among people whose politics you share.

Two problems arise when people do not make this distinction between the personal - psychological traits or character - and the political - sets of ideas or stances on issues of policy.

The first is a tendency to use partisan motivated reasoning to work backwards from political positions to principles to personality traits to character. You voted for X, therefore you hold these values, therefore you have this kind of psychology, therefore you're a bad person. In my case, when voting Labour on the grounds of its economic and social policies, I lost Twitter followers based on reasoning that looks like this:

You voted Labour.

Therefore, you support antisemitic rhetoric/don’t know what a woman is.

Therefore, you are a racist and a misogynist.

Therefore, you are a despicable human being.

For others, it could look more like this:

You voted Conservative.

Therefore, you support anti-Muslim rhetoric/don’t care about working class people.

Therefore, you are an anti-Muslim bigot, racist and want children to starve.

Therefore, you are a despicable human being.

This is a form of extreme ideological blinkeredness and failure of theory of mind. The right is certainly not immune to it (as indicated by my own experience), but the self-righteous, moralistic scolding attitude is more evident on the left. It both undermines the credibility of the left and drives polarisation. If you find you are prone to falling into these patterns of thinking, I recommend Ilana Redstone’s The Certainty Trap which includes useful exercises for practicing thinking about reasons people may take different stances from you other than ‘being evil.’

The second problem with failing to distinguish personality from politics is that people who are genuinely being abusive, dishonest, authoritarian, expressing cruel or hateful views that most people find appalling or simply being insufferably zealous and unpleasant to be around then claim that they are being shunned for their political views and are the victims of intolerance. This is less common on the left who, when they wish to claim to be the victims of unreasoning hatred, will usually find an identity-based reason to do so. It is more common to see dishonest and illiberal people on the right seize upon the trope of ‘the allegedly “tolerant” left being intolerant again’ to claim they are being shunned for being a conservative when they are, in fact, being avoided for behaving in ways that are intolerable.

If a left-wing family member or a friend is avoiding you, therefore, it is worth asking yourself, “Is this because I said I think we need tougher measures to deal with criminally offending undocumented migrants than the left is currently offering or was it that I laugh gleefully about families trying to follow immigration procedures being torn apart?” “Have my nephew and his husband stopped talking to me because I am conservative or was it all that stuff I said about gay men being paedophiles who should not be allowed to marry, let alone raise children?” or “Have I not been invited to the family Thanksgiving because I mentioned having voted for Trump or is it because I behave like this and ruin everybody’s day?”

If you are not exhibiting personality traits and behaviours that you could see might be deeply unpleasant to be around if you put yourself in the other person’s position and are not demanding that your friends and family tolerate this behaviour or be branded intolerant leftists engaging in Cancel Culture, then you may well actually be a victim of an intolerant leftist who is weaponising strategic shunning against you. You’d still have to respect their right to freedom of association, but the problem lies with them and you can justly criticise their unwillingness to see past political differences and their self-righteous attempts at behaviour modification, and decide that they are not people you wish to associate with either.

The New York Times piece and the responses to it were revealing of the important distinction between strategic shunning, which is about creating social pressure to induce or shame people into pretending to hold views they do not hold and the organic distancing that happens when people realise they simply don’t like each other or enjoy each other’s company. The former is corrosive to social trust, exacerbates polarisation and destroys relationships without achieving anything (because ballot boxes are private). The latter can be a natural part of life that indicates that people have changed and this may or may not mean that anybody has done anything wrong. We shouldn’t confuse them.

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has hit 5000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.75% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2025 is to increase that to 7%. This will enable me to keep doing this full-time into 2026! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

This issue has been very painful for me. Working in the arts, the majority of people I’ve known in my life either strongly support CSJ, pretend it’s not as dangerous as it is, or know how bad it is but are too afraid to speak up - possibly because they saw what was happening to me. I’ve had to let many of these relationships go because it became intolerable to constantly discuss abstract CSJ ideals with them while trying to get them to see how these ideas, when they are implemented, hurt people like me - the “friend” sitting right in front of them. These conversations became so frustrating I once said to a long term friend in a restaurant, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed is the foundational text of the graduate program you work in. If you teach “oppressor/oppressed” ideology you must know who oppressors are. Who in the restaurant is an oppressor? Is it him? Or her?” Not surprisingly, that didn’t work. Nothing seems to. It was hard to accept that I either needed to find a way to tolerate what became intolerable or walk away for my own well-being.

Excellent ways of making distinctions between personal and political. Thank you!

I have a quick and simple test of seeing if someone is ideologically captured. Ask them to list four policies or positions they disagree with, coming from the party or the politician they support. Then ask them to list four policies or positions they agree with, coming from the party or the politician they oppose. If they are not capable of doing either, they are ideologically captured.

Would you agree with that?