The Difference Between Incitement and Being a Callous Arsehole

And why we should not contribute to the tyranny of prevailing opinion.

(Audio version here)

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has over 5000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.75% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2025 is to increase that to 7%. This will enable me to keep doing this full-time into 2026! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

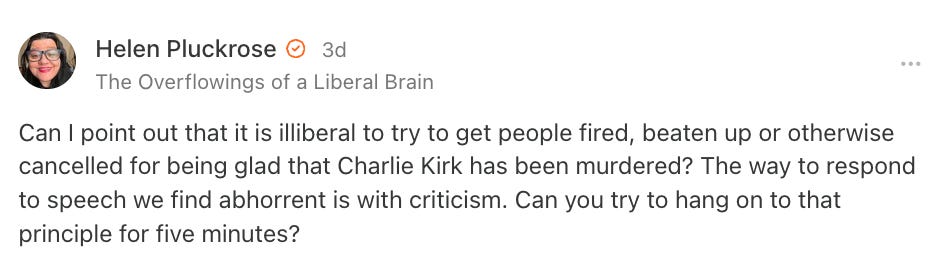

I recently caused a great deal of anger on social media with this post:

Hundreds of people on the hell-site that is X accused me of wishing Charlie Kirk dead, of being hypocritical and not having cared about cancel culture when it came from the ‘woke’ left, of being evil and in support of political violence and of being fat. Only the last of these is true. I have utterly condemned political violence generally and the murder of Mr. Kirk specifically and appealed to ethical people on the left not to ignore the hateful comments or to “whatabout” or otherwise evade the issue of left-wing justification of political violence. (We still do not know that this murder was inspired by left-wing politics but the principle remains). I have also been opposing the identitarian left’s Cancel Culture full-time for a decade.

More reasonable people have responded, also in their hundreds, that it is perfectly reasonable for employers not to want to employ someone who justifies political violence, especially if they work in positions of responsibility with a politically diverse public. I would not refute this, but would suggest that there is an important distinction to be made between the assessments employers have to make with regard to whether an employee poses a risk to others or to the reputation of their business and a culture of political activism which sees people searching the internet for people saying things they find appalling, summoning a mob to ‘make them famous’ and then pressure their employer to fire them. The first of these involves policy-based risk assessments, which are not of particular interest to me. The second is revealing of our growing culture of polarisation and punitive political warfare, which is certainly a problem I am concerned about.

Feelings are running extremely high at the moment and understandably so. For many on the right, who admired Mr. Kirk, his murder, while engaging civilly in debate with people with whom he disagreed, is ample evidence that the liberal approach of responding to ideas we dislike with criticism and reasoned argument is an idealistic fantasy that does not reflect our political reality. It is not only ludicrous for me to suggest such a thing, but deeply offensive. With my reference to established arguments against cancel culture, am I seriously suggesting that public endorsement of the murder of a human being is equivalent to posts about race, immigration or gender identity that could be considered problematic if one takes a particular theoretical stance? Do I not realise that a young father is dead and people are gloating about it and celebrating it?

Yes, I do. Comments about Charlie Kirk’s death must inspire deep revulsion and outrage in anybody with a shred of empathy. It must also cause intense alarm in anybody who is already concerned about the rage, contempt and dehumanisation currently being thrown across political divides. As Mike Young recently put it,

People who celebrate the murder of their political opponents are not participating in the marketplace of ideas, they are encouraging deadly political violence by building a permission structure to legitimize and justify the murder of those they disagree with.

We need a strong consensus that, no matter how strongly we may disagree with somebody and even feel that their contribution to public discourse is harmful to society, violence is never an acceptable response.

Nevertheless, even in moments like this - perhaps especially in moments like this - we must distinguish between hateful political ranting and genuine incitement to violence. To blur that line in the heat of outrage is to risk eroding the very principles that protect us all.

In the UK, we have been debating this very issue for several months in the case of Lucy Connolly who issued this tweet which she deleted a few hours later:

Those who felt the sentence was justified argued that she had incited people to burn down migrant hostels full of human beings at a time when tensions were already inflamed, and when people did in fact attempt such attacks, injuring police officers and damaging emergency vehicles. She had also called for the murder of elected members of government. Those who felt the sentence was unjust argued that her post was not a literal incitement to political violence but an emotional rant in the aftermath of the murder of three little girls. They noted her phrase “for all I care” indicated not encouragement but indifference, and stressed that no direct link was found between her words and the later attacks. While most agreed her sentiments were abhorrent, they insisted we must maintain a very high bar for what counts as incitement before criminal charges are justified.

Defenders of freedom of belief and speech must separate two questions: is a belief or stance hateful, offensive, or morally repugnant and should it be penalised? All reasonable people can agree that, for a healthy society, we need people not to be OK with the murder of political activists or the burning of migrants or politicians alive. But that agreement does not settle whether legal or social penalties are justified.

The liberal position is that only direct and material harm to others justifies coercion or punishment for speech. As John Stuart Mill put it in On Liberty:

[T]he only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right. These are good reasons for remonstrating with him, or reasoning with him, or persuading him, or entreating him, but not for compelling him, or visiting him with any evil in case he do otherwise.

It is crucial that the bar for what constitutes harm be set very high. In the debates over Lucy Connolly, her defenders pointed out that no direct link was found between her words and the violence that followed. Those who believed her sentence was appropriate argued that she had nevertheless encouraged and legitimised such acts, and was therefore complicit.

We can and should certainly have serious conversations about what kind of rhetoric falls into the realm of ‘irresponsible’ and could contribute to the normalisation and justification of violence or hatred. Nevertheless, I think we should be wary of penalising people for contributing to discourses that can hypothetically result in harm. This has frequently been used to stifle debate. Many of us have criticised Critical Social Justice activists for insisting that gender critical feminists and social conservatives expressing their disbelief in and opposition to the concept of gender identity contribute to a culture in which trans people become the victims of violence or commit suicide. Similar criticisms were made of those who claimed people who said Donald Trump was a threat to democracy were complicit in the attempt on his life. We must be able to raise strong criticisms of social issues.

It could be argued that positions which contain a genuine argument should be protected as part of legitimate political debate, whereas provocative statements that implicitly condone violence fall outside that protection. Consider, for instance, the slogan printed on t-shirts: “A good kick in the balls will solve your gender confusion.” It adds nothing meaningful to discussion and, taken literally, advocates violence. Similarly, Kyle Gass’s quip, “Don’t miss Trump next time,” is not a critique of the president but, taken literally, a call to harm him. Yet both are best understood as tongue-in-cheek expressions of contempt, not serious attempts to incite violence. People must be able to express strong feelings too, without being afraid they will be taken literally. There are real grey areas where a statement can plausibly be read either as hyperbolic ranting or as genuine incitement. These need to be argued out case by case. Nevertheless, the bar must be intent to cause direct and material harm, not the vague, subjective, and easily manipulated accusation of “contributing to a harmful discourse.”

There are those who will argue that I am missing an important distinction between legal penalties and social disapproval or consequences in one’s professional life. We should have a very high bar for the law penalising people for speech but surely citizens can make their own judgements about what is morally acceptable and reflect this in social disapproval? Lucy Connolly, as a childminder, could legitimately lose clients because parents decide not to leave their children with someone who fantasises about burning people alive. This would be a perfectly liberal exercise of freedom of association. Likewise, employers must be free to make an ethically sound, reasoned assessment that people who celebrate political violence present a risk to the safety of the workforce or customers or to the reputation of the company without being accused of engaging in cancel culture.

This is where it becomes important to consider the cultural side of Cancel Culture. By ‘culture’ I mean the wider social norms that extend beyond workplace policy. These norms still shape what employers feel pressured to punish, but they are not reducible to questions of HR or reputation. We do need liberals thinking carefully about where the line lies between reasonable workplace expectations and interference in employees’ freedom of expression in their lives outside work. Individual cases in which an expressed position may arguably make someone unfit for a job or damage an organisation’s reputation, can and should be considered case by case. But this is not my primary concern. My concern is the state of political discourse itself, our deepening polarisation, and what it is doing to our culture more broadly. I fear returning to a culture which empowers mob rule and makes people very vulnerable to whatever moral orthodoxy holds sway at any time.

I am concerned about the direction in which our cultural norms are going with regards to the weakening of commitment to free speech, the drive to impose certain social norms on everybody and to punish dissenters. This became known by the term ‘Cancel Culture” when imposed by adherents to the Critical Social Justice movement but it is certainly not new. It reflects a longstanding human tendency to authoritarian social engineering in the service of a dominant moral orthodoxy. Some have attempted to define it more narrowly and without reference to historical precedent. I could not disagree more strongly with the otherwise estimable Rob Henderson’s recent claim that Cancel Culture is defined by the attempted imposition of social norms that have not yet been established. On the contrary, this is the mechanism by which socially conservative norms have consistently policed themselves and have included penalising people for expressing views that include “Maybe God does not exist,” “Women should have the same legal rights as men” and “It’s OK to be gay.” In some countries it still does. We are surely not going to tell human rights campaigners that they are not really being cancelled when penalised for expressing these views, because the social norms they oppose have been established for a long time?

We can be very sure that Cancel Culture is not new because liberalism - the philosophy centred on protecting individual liberty - arose explicitly to oppose it. It did so, not only to protect people from state interference, but also from what has been referred to in liberal philosophy as ‘the tyranny of the majority’ or - more aptly because a small number of vocal agitators can overrule a passive majority - ‘the tyranny of prevailing opinion.’ Again, John Stuart Mill is valuable. Writing in 1859, the problem he is referring to and the impact it has on the human psyche, is instantly recognisable as what we now call, ‘Cancel Culture.’

Like other tyrannies, the tyranny of the majority was at first, and is still vulgarly, held in dread, chiefly as operating through the acts of the public authorities. But reflecting persons perceived that when society is itself the tyrant—society collectively, over the separate individuals who compose it—its means of tyrannizing are not restricted to the acts which it may do by the hands of its political functionaries. Society can and does execute its own mandates: and if it issues wrong mandates instead of right, or any mandates at all in things with which it ought not to meddle, it practises a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression, since, though not usually upheld by such extreme penalties, it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself. Protection, therefore, against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough: there needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling; against the tendency of society to impose, by other means than civil penalties, its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them; to fetter the development, and, if possible, prevent the formation, of any individuality not in harmony with its ways, and compel all characters to fashion themselves upon the model of its own.

What Mill opposed was precisely the culture of social coercion that we see rising again in our own age, where conformity is demanded not only by governments but by fellow citizens.

As the beneficiaries of the development of liberal concepts of individual liberty - the United States is founded upon them - we must not fail to recognise threats to them. Even when the views people are being cancelled for are those we have absolutely no sympathy for and believe society would be far better off without, we must think in terms of the long-term game plan and the bigger picture. The dominant moral orthodoxy whose values you share and which has the power to cancel people right now is unlikely to hold sway forever. Do you really want to contribute to the further weakening of commitment to individual liberty and freedom of expression, knowing that, with a change of government or of public opinion, the views which become cancellable may well be your own? If so, please have the honesty to say not, “This isn’t really Cancel Culture” but “I support Cancel Culture when it aligns with my own views.” If not, please recognise and consistently oppose the rising culture of cancellation.

Fortunately, this opposition can be mounted at the individual level, in the way we choose to act. To do so, we need to separate out the strands of the issue. One strand is the responsibility of employers to ensure an ethical workplace, protect customer trust, and safeguard the reputation of their business. Another is the growing normalisation of a politically punitive mob mentality, in which people prioritise finding and punishing “wrongthinkers” over engaging seriously with ideas.

In practice, these things often overlap. But in principle, at the level of individual ethical decision-making, they are separate. If you are an employer, your duty is to consider the details of a specific case and make a fair assessment of whether a stated opinion genuinely affects someone’s ability to do their job or whether it is none of your business. If you are a political activist, your duty is to ask whether your time is better spent scouring for people to punish, or engaging seriously with ideas.

Too often, people engaging in Cancel Culture try to distance themselves from the human cost of it and present it as some kind of naturally occurring phenomenon. They say things like “Freedom of speech is not freedom from consequences” as though they are not involved in deciding who should face consequences, for what transgression and what those consequences should be. They speak as they might about somebody who decides to climb a mountain having to accept the possibility that they might fall off. But culture is not a natural force like gravity. It is something we each play a part in cultivating. We should each think carefully about what kind of culture our actions are attempting to build.

If, on serious ethical reflection about a certain incident, you think you have strong evidence that somebody is a danger to vulnerable people and that you have a responsibility to inform their employer of this, you should do so. Make sure that your ethical justifications are well evidenced, soundly reasoned, consistent across political divides and not issued in the service of your own political ideology in a way you would not like to have somebody else’s imposed on you.

If, on reflection, you find that you are searching for people saying things you oppose in order to punish them, fuelled by your own feelings of outrage, disgust and, in the case of the murder of Charlie Kirk, grief, please stop and consider the bigger picture. Think about what such actions contribute to culture and whether this is a culture you wish to build. Consider whether you might do better to make an ethical argument against that person’s stance and persuade others to oppose it for good reasons. Think about whether contributing to a culture of cancellation could backfire on you if your own political views fall out of favour.

Ultimately, the culture we build will not be measured by how harshly we punished our enemies, but by how steadfastly, even in times of rage and grief, we defended the liberal principles that protect us all.

Here is a related post worth reading: https://open.substack.com/pub/andrewdoyle/p/the-oxford-union-and-the-free-speech?r=23ix4k&utm_medium=ios

This is a timely reminder of how Mill's warning against the tyranny of the majority hasn't aged a day, and I appreciate how this piece of writing shows Mill's defence of free speech and free expression is the most important argument we have.