Why Liberalism Isn’t Centrism (and Never Was)

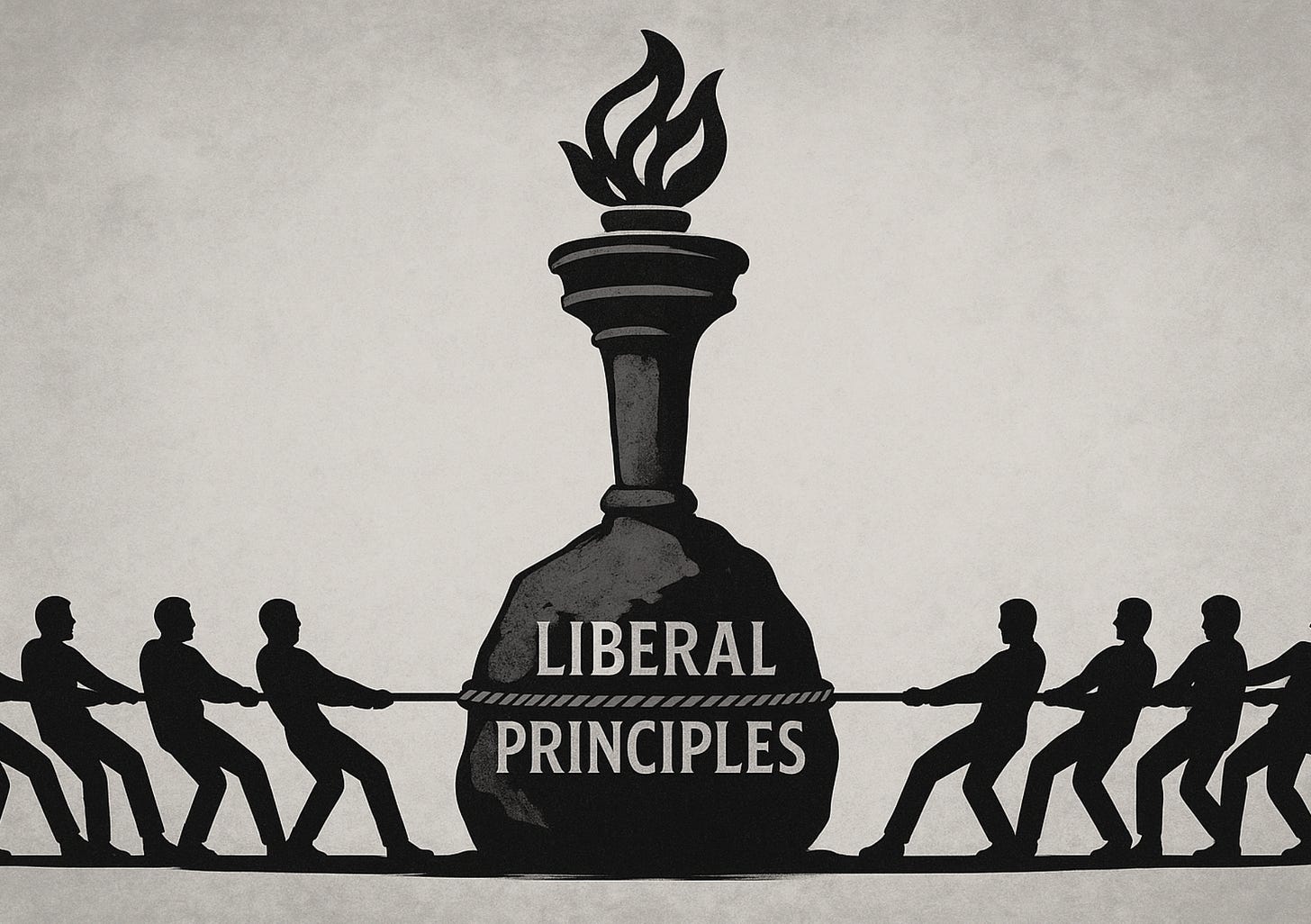

Liberalism is a radical commitment to liberty

(Audio version here)

Recently this post was made on Substack.

I responded somewhat facetiously to this with,

This, predictably, led some readers to assume I was advocating for taking a “middle” stance on principle, as though centrism were a moral position in itself. Of course, I wasn’t. I was, as always, advocating for reasoned and robust debate across political divides, and against the illiberal factions who want to shut it down. In other words, I was arguing for liberalism.

But the exchange did highlight something worth explaining again: the difference between centrism and liberalism.

The responses to me can probably best be encapsulated by this post:

Me too — but this comes down to a misunderstanding of centrism versus consistent liberal principles.

People who think in terms of “centrism” tend to see principles as relational rather than consistent. They see them as defined by where someone stands, not by what one stands for. Anyone who genuinely tried to place themselves in the exact middle of every dispute between left and right would indeed be a relativist. Their virtues and values would shift with the political winds. Their morality would always be based on their position and not on any principles.

Perhaps people with such commitments exist, but I’ve never met one.

In reality, many principled people who currently find themselves in the “centre” do so because that’s where their values have placed them. Liberals — those who value individual liberty — are here now because our commitments to democracy, free expression and freedom of belief put us at odds with both the authoritarian “woke” and the authoritarian “anti-woke.”

The liberal goal to protect democratic processes, freedom of belief and speech and viewpoint diversity makes us look conservative to the radical left, because we are trying to conserve the liberal philosophical underpinnings of Western civilisation. It makes us look progressive to reactionaries on the right, because we refuse to roll back the hard-won protections for freedom of religion and individual liberty and recognition of equal rights regardless of race, sex, or sexuality. They both accuse us of protecting the ‘status quo’ because they both see the ‘status quo’ as the norms of society they don’t like. And they are united in seeing individual liberty as central to that even though the societies they envision which would deny that liberty are radically opposed.

We are constantly being urged to become just a little bit (or a lot) illiberal in one direction or another. Just ban this kind of speech and these books. Just penalise people expressing these views. Just require these affirmations. Just deny these people the same right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness as everybody else. We decline and so we are ‘stuck in the middle.’ People who think in terms of political position rather than in terms of principles then see us in the centre and claim that this ‘centrist’ position defines and drives our stance. They assert that we would also have been in the centre on other issues, even those, like slavery. that directly concern the freedoms we actually define ourselves by. Perhaps this is because they themselves incline towards to radicalism and will take the radical position in any political situation rather than holding consistent principles?

On the contrary, as Alex Mercedes points out, liberalism has often been the radical position. The commitment to individual liberty drove the American Revolution. It underpinned the abolition of slavery and the movements for women’s suffrage and civil rights. The fight for freedom has always been radical and it has always been liberal. It continues to drive many radical movements in other parts of the world today.

Those of us who live in liberal democracies now have the rare good fortune of inhabiting societies that already abolished slavery, established constitutions and built norms protecting freedom of belief, speech, and equality before the law. We have never achieved a perfectly liberal society and probably never will because humans are not a perfectly liberal species. There will always be authoritarians to oppose. Nevertheless, compared with the historical and global alternatives, we’ve done remarkably well.

This puts us in the position of trying to preserve and more fully realise those liberal principles rather than having a radical revolution to achieve them. We appear to be in the “centre” because we are actually trying to preserve the status quo of the philosophical liberal underpinnings of Western modernity against radical forces on the left and reactionary ones on the right.

This is far from a commitment to taking a centrist position! I fear that as polarisation deepens and illiberal movements rise on the left, right, and in Islamist forms, the liberal defence of individual liberty, free expression, democracy, and equal rights will once again come to seem radical. Our task is to ensure it doesn’t and to keep liberalism alive as the moral centre of a free society. This is not a wishy-washy commitment to “centrism.” It is a radical commitment to liberty.

We are not centrists. We are liberals. And the future of Western liberal democracies depends upon ours remaining the mainstream position.

As I wrote in the launch of The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain:

Liberalism is the underlying philosophical framework of liberal democracies and, consequently, the defining feature of Western civilisation. If you hold the following values, you are, in the most fundamental sense, liberal:

A commitment to individual liberty - freedom of belief, speech, association (individualism)

Tolerance of difference and a will to live and let live as well as a recognition of the value of viewpoint diversity to advancing knowledge and resolving conflict in a democratic society (pluralism)

Recognition of our shared humanity and the common rights, freedoms and responsibilities this bestows upon us all (universalism),

A drive for reform over revolution or reactionism as a model for resolving societal problems.

A commitment to actively protecting others’ right to believe, speak and live as they see fit, provided they do no material harm to anyone else nor deny them the same freedoms.

The belief that all people come into the world with the same right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness and this can only justifiably be removed from any individual due to their own demonstrable harmful actions.

An understanding that threats to freedom come not only from the state but from authoritarian ideologies, individuals and groups, so liberal principles need to be protected not only in law but widely understood and valued in society.

A belief that it is in the interests of the overwhelming majority to conserve liberalism and the liberal democracies within which it flourishes.

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has over 5,500 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.75% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2025 is to increase that to 7%. This will enable me to keep doing this full-time into 2026! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

I think I want to apply my understanding of your thoughts on liberalsim to a critique of gender critical argument. I have suggested that the argument of biology vs ideology is problematic for us gen crits making it. I have suggest it's better that we make the case it's the ideology of self-identified-genderism vs an ideology of based on biology.

I have gotten well argued push back when I claim that a man has a right to think he's a woman and a woman has a right to do the same. Its only a problem when either wants to compel others through legal or other means.

i submit it is illiberal to claim a man is thinking wrong as a matter of fact.

It's taken me an embarrassingly long time to figure out that my "political home" is liberalism. For most of my life I've been fairly moderate (and somewhat inconsistent) on economic issues, but more radical on issues of liberty. In the US, we had libertarians, but they always seemed too crazy to follow, like taking liberty and divorcing it from all other considerations, where I look at liberty as the most important of many competing considerations.