Liberalism Lives, But We’ve Forgotten How to Live It

A historical case for seeing liberalism not as background noise, but as a living civic responsibility

(Audio version here)

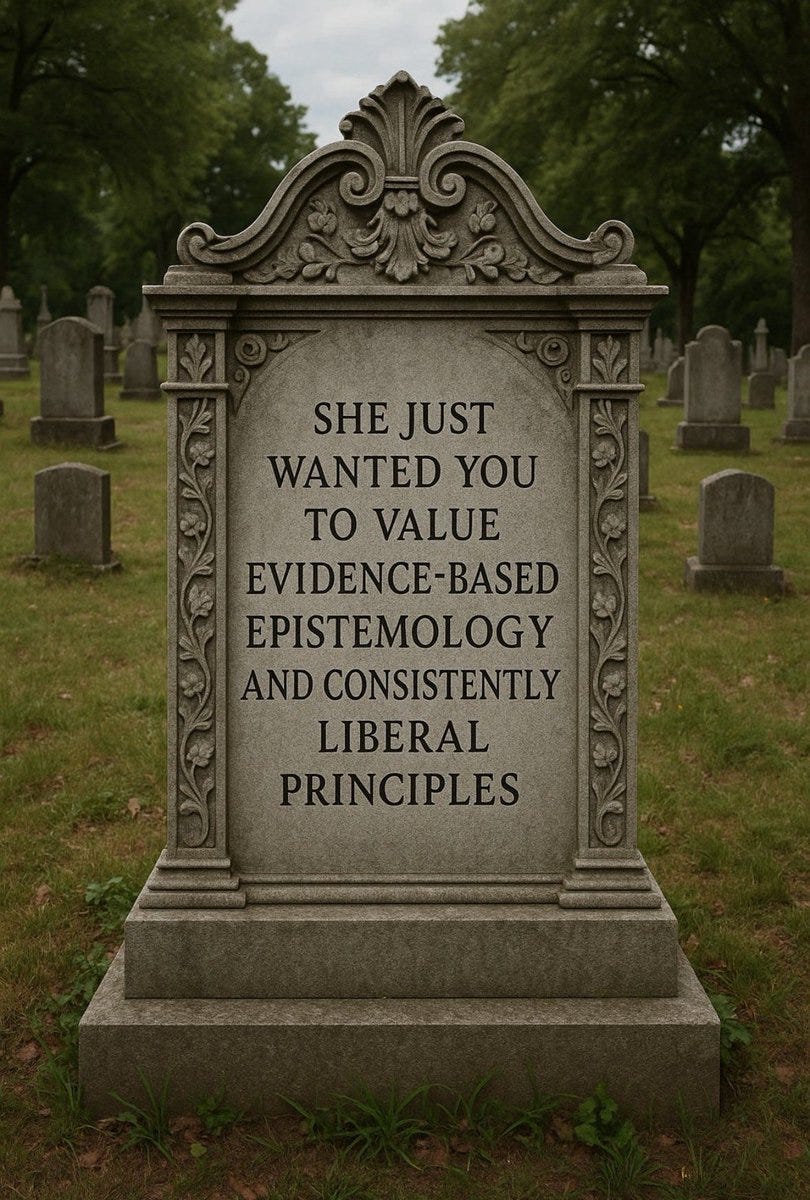

I have left instructions in my will for my gravestone to have an epitaph that reads “She just wanted you to value evidence-based epistemology and consistently liberal principles.”

Right now, it can often feel as though it is liberalism itself that needs an epitaph. However, to think this way is not only to risk enabling a self-fulfilling prophecy, but also overlooks the extent to which we still think in liberal ways, even when being illiberal! This longer piece intends to look at how this pattern of thinking emerged, the way it still runs in the background of common arguments and how we can bring it back to the forefront.

We have been seeing an explosion of illiberal partisan narratives that seemingly have no concern at all for what is true accompanied by terrible and inconsistent reasoning in service of one political ideology or another. As we become increasingly tribalistic and polarised and factions on both the postmodern left and post-truth right dominate online discourse, emotionally resonant stories and appeals to “lived experience” are stated confidently in utter defiance of demonstrable reality. At the same time, motivated reasoning and confirmation bias abound and principles seem infinitely malleable as people endeavour to justify things in one context that they utterly reject in another.

Many liberals have been expressing a certain degree of despair and sense of futility about the ongoing degradation of the standards of political discourse and dearth of consistently applied principles, especially online. It is hard to see how a marketplace of ideas can help us out of our current culture war if people simply do not care about what is true or about making consistently principled arguments about what is right. I sometimes succumb to this despair and become inclined to believe that those who say that liberalism has died are right. Not because liberalism as a political philosophy has failed, but because so many people are failing to do it.

As Mike Brock wrote recently,

Here’s what most people miss: liberalism is epistemic before it’s political. It’s fundamentally about how we know things and how we organize knowledge in societies. The political arrangements—democracy, constitutional government, individual rights—flow from deeper commitments about truth and reasoning.

Our commitments to truth and reasoning seem to be on life support right now. As someone whose academic background focused on the late medieval period in England, I fear going back to a time before Western modernity arose and made those commitments. This was a time in which authoritarianism and tight controls on what people may believe and say and how they may live were simply the norm. The only thing that changed was which authoritarian dynastic or theocratic regime held sway and dictated who one must pay homage to and what one must believe or not believe. The liberal idea that people should be free to believe, speak, and live as they see fit, so long as they cause no harm to others was not part of cultural discourse. Nor was the notion that such freedom could be used to advance knowledge or resolve conflict. Received wisdom constituted knowledge and conflicting ideas were dealt with by force.

The use of authoritarian methods to impose controls on belief, speech and lives was not considered to need justification. This was simply what authorities did when they presumed absolute knowledge of what was true and good. They enforced it as “The Truth” and a “common good.” Of course, this was never universally accepted as true or as good because humans don’t work like that. This is why religious and secular factions continually form and why authoritarian regimes always ultimately get knocked violently aside by another, causing great collateral damage in the form of everyday people.

The Emergence of Liberalism

Liberal principles would have made very little sense to people living in my period of study - the late medieval period in England. Letting people believe, speak and live as they see fit provided they are not harming anybody else would have seemed a strange and radical notion to even the most philosophically inclined. I suspect most everyday people simply would not have understood the proposition they were being presented with. Individual autonomy? Isn’t that just pride and self-will?

There is a longstanding argument among late medieval and early modern historians about whether the individual even existed in the medieval period - whether people could perceive themselves as distinct individuals with their own unique minds, desires, and personalities. The view that they could not was expressed most plainly by the Swiss historian, Jacob Burckhardt, who claimed that in the Middle Ages, “man was conscious of himself only as member of a race, people, party, family, or corporation” (1887). To Burckhardt, this really was a matter of consciousness; people were incapable of having a concept of themselves or others as individuals distinct from the hive mind of their collective.

I have argued that this is to take social constructionism entirely too far. We are not ants. We are a species of primate that has lived in relatively small hierarchical groups within which every individual was known to every other individual for millions of years. Our big brains developed to form cooperative bonds while competing individually for resources and mates, building individual reputations to do so and developing sophisticated ways to evaluate others and detect freeriders. Humans are distinctive in that we have a form of relationship known as friendship, in which we connect with and support humans to whom we are not genetically related because we like their personalities and find them compatible with our own. These traits cannot be socially quashed.

Of course, individuals have always existed. The concept of the individual has also always existed. Arguments against this invariably provide evidence of it. There is much surviving moralistic writing telling people to think of themselves in terms of the virtues assigned to their collective - class, sex, etc. - and to conform themselves to dogma, but this would hardly have needed to exist if people had already been doing that.

Two things can be true at once, and I would suggest they are:

Human individuality has always existed and has always been recognised to exist

Prevailing authorities have always taken steps to quash this and make people conform to their vision of the ‘common good’

We could then add to that the well-evidenced observations that:

Trying to make people conform to a single vision of the common good has never worked in the history of humanity, which is filled with religious, dynastic, and cultural factionalism and bloodshed

People work together most productively and resolve conflict most peacefully when differences are allowed to exist and to be argued out in a form of collaborative combat

The development of liberalism in which people are allowed to hold their own beliefs, express them, and live by them provided they do no material harm to anybody else nor deny them the same freedoms has provided the best system of conflict resolution the world has ever known, while rapidly advancing knowledge production and human thriving.

To Burckhardt, the development that lifted the veil from human consciousness and enabled them to recognise themselves and others as individuals was the Renaissance. This expansion of topics of legitimate interest, rediscovery of ancient philosophy, and invitation to contribute to multiple forms of knowledge production and art were certainly revolutionary to the development of intellectual autonomy and individual interests (at least for wealthy, educated people). At the same time, the Reformation - with its stance that individuals should be allowed to interpret scripture for themselves - also facilitated some degree of spiritual autonomy as well as literacy, and was also open to everyday people, including women.

The ability to question received wisdom about the correct way to interpret scripture enabled people to consider that it might not be true at all. We can know that atheism was starting to play a part in public discourse by the 1590s, not because people were publishing arguments in support of it (this still carried the death penalty), but because treatises arguing against it suddenly emerged. The growth of scepticism ushered in Enlightenment rationalism and then the Scientific Revolution. The growing volume of differing opinions and belief that one should be able to explore these and have a say in the running of society and not be unduly constrained by the state or church led to the development of liberal philosophy and the liberal democracies which now define Western civilisation. This same expansion of intellectual freedom and pluralism fostered an innovative, collaborative and competitive ethos that underpinned the rise of capitalism, arguably the most materially productive element of the development of liberal thought.

This culture of challenging old beliefs and reforming old systems gradually brought about an increased tolerance of religious minorities. Barriers preventing Catholics and Jews from entering universities and professions were removed. Rigid class structures began to weaken as the idea that there were innate classes of people that ruled and classes that were ruled was challenged. This opened up the possibility of social mobility and a more representative participation in democracy and civic life. There gradually grew an acceptance that women should be regarded as competent adults and allowed more autonomy. They became able to own property, take part in democratic processes and enter professions. Eventually, they gained the same access to loans and mortgages that enabled them to start businesses and buy homes that men had and to be paid equally for their work. The long-held belief that homosexuality was a form of depraved sinfulness to be condemned gave way to a belief that it was a disorder to be pitied and then that it was just something some people were and did not need either prosecuting or treating.

It is important to fully appreciate that these latest shifts towards individual autonomy happened very recently. My mother faced the problem of being a single woman trying to get a mortgage without a male guarantor and having to wait for her younger brother to establish himself in a career before she could do so. My uncle fled England as a young man due to police investigations into his sexuality on the grounds of (justified) suspicions that he was gay.

The history of race relations in England do not fit neatly into this evolution of ideas because there is no long history of racial groups living alongside each other with one being subordinated to the other. America, which established religious tolerance earlier, women’s and gay rights at about the same time and did not ever have the same rigid class structures as England, bears witness to the evolution of liberal ideas in relation to race and the growing acceptance of black Americans as full human beings with the same right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness as white Americans. Living Americans remember racial segregation.

Liberalism developed on multiple fronts but it is vital to recognise the driver for all of them as fundamentally a ‘freedom’ principle. The liberal drive is towards the removal of constraints and barriers. Liberalism in Europe has always had a strong conservative strain which holds that most of the systems and institutions of society are good and have been created for good reason and should be conserved. The problem has been that some groups of people were being unjustly excluded from participating in them. Therefore, any ideology that shifts from ‘People must not be prevented from…’ to “People must be compelled to…” is not liberal, even if it claims to be progressive and describe itself as a continuation of civil rights movements. People who claim that liberalism ushered in illiberalism - e.g., letting gay couples get married led to everybody being compelled to accept trans identity; letting racial minorities have equal access to everything led to authoritarian anti-racist training sessions - are entirely missing the essence of liberalism: individual autonomy.

Any movement that wishes to overthrow liberal foundations in revolution to impose its own values on everybody by fiat also cannot be considered liberal even if it claims to be progressive and theorises that its endeavours will result in greater freedom. Liberalism does not preclude the possibility of revolution when the pre-existing system cannot be reformed via democratic processes and robust public debate open to all. When it can, however, attempts to bypass this process are illiberal. The American Revolution was waged in order to free the citizens of the country from external constraints and establish a liberal society, not overthrow one, and it remains the clearest example of a liberal revolution. Its resultant constitution is liberal and the aim to conserve those liberal foundations is conservative. It is in this way that liberalism and conservatism can be recognised as overlapping principles that can be and are held by many people completely coherently.

The liberal philosophical tradition has many facets. Some key thinkers have focused on the freedom of markets, others on freedom from state control, some on religious freedom and freedom from religion. Many have prioritised freedom from ‘the tyranny of the majority’ or from social pressure that amount to interference in the lives of individuals by dominant moral orthodoxies. Others have focused on academic and artistic freedom or the free exchange of ideas more broadly to advance knowledge and resolve conflict. Some have focused on specific groups being treated in an illiberal way and sought to remedy this and remove barriers to their individual autonomy and inclusion in all that society has to offer. Key to all this, however, is the notion of individual liberty and the simple premise:

Let people believe, speak, live as they see fit, provided it does no material harm to anyone else, nor denies them the same freedoms.

This premise has never been upheld perfectly. Liberalism is an ongoing evolving practice to recognise illiberalism - old and new - and reform it out of existence or prevent it taking root in the first place. There have always been ideological factions fundamentally opposed to it and demanding authoritarian control of people’s beliefs, speech, and non-harmful lifestyles and certainly always will be. Nevertheless, the fundamental liberal principle - of allowing different views to exist and be spoken, and other people to live in ways that one oneself would not - did gain widespread cultural acceptance and was gradually internalised by the inhabitants of liberal democracies.

It became an expectation that, in order to demand that something not be allowed, one must provide a justification based on harm, rather than, as my late medieval people would have expected, that it was against the teachings of the church or the mandates of the monarch or the expectations of the class or sex roles one was born into. This consensus has been internalised to the extent that most people continue to hold the idea that they should leave other people alone unless they are harming anyone on an intuitive level, even if they do not think this through philosophically and articulate it in terms of first principles.

The Case for Hope

The tortuous and inconsistent motivated reasoning so common in currently popular arguments is both infuriating and depressing. Nevertheless, it offers grounds for hope that rumours of the death of liberalism are premature. This is because it is characterised not by straightforward authoritarian demands - We are right so everybody must do as we say - but by desperate mental gymnastics to pretend that one’s own brand of authoritarianism is not, in fact, authoritarian. The epistemic basis of liberalism in which there is an expectation that truth claims will be evidenced and arguments soundly reasoned is also highly intermittent and inconsistent in current political discourse, but not absent.

For examples,

“Lived experience” is frequently claimed to be a valid way of deciding what is true that only those callously indifferent to the experiences of others would demand justification for when argued from by people we agree with. Nevertheless, it becomes clear that it is a terrible epistemology and should be dismissed unless supported with evidence and reasoned argument when claimed by a political adversary,

When a set of controversial political ideas or a public figure is criticised, it is common to see zealous advocates and apologists pathologise this as evidence of some form of ‘fragility’ or ‘derangement syndrome’ to discredit the critique without further examination. Some things are so obviously right and good that they are ‘not up for debate.” However, when people meet such resistance themselves, they frequently reach for liberal arguments that everything is up for debate, nobody is immune from criticism and people making truth claims and arguments should be expected to respond in good faith to their critics.

It seems clear to many that their own offended or disgusted feelings constitute objective evidence that what someone else is saying or doing is so morally wrong that it should not be allowed. But they typically remain quite capable of arguing well that those with whom they disagree should stop being a snowflake and take responsibility for their own offended or disgusted feelings rather than making them everybody else’s problem.

Furthermore, people using such inconsistent reasoning frequently explicitly appeal to spurious concepts of harm or engage in dubious reframing of issues of freedom to justify their authoritarianism. These are the liberal principles underpinning their culture which they still hold intuitively and which they know others to hold intuitively.

For example, in order to justify de-platforming a gender critical feminist, trans activists will commonly say that their beliefs promote transphobia which causes trans people to get murdered. They make a (bad) case for harm - the one ground upon which liberalism justifies coercion or censorship. This claim can be countered with arguments that no trans person has ever been murdered by a feminist or by people inspired by feminism.

We saw the same phenomenon when illiberal supporters of Donald Trump claimed that arguing him to be a threat to democracy inspired the assassination attempt against him. Again, this is harm and needed to be addressed with arguments about the importance of being able to criticise political leaders, especially if one believes them to be a threat to the system of democracy. We cannot refrain from ever criticising anyone in case it inspires somebody else to shoot them.

Alternatively, those who wish to de-platform gender critical feminists commonly move the goalposts and say that nobody is entitled to a platform and many people did not wish to offer them one. This is an attempt to refute accusations that they are denying freedom by implying that it is the feminists being entitled and seeking to impose themselves where they are not wanted. This can be responded to by pointing out that other people had already offered them a platform, and the de-platformers are attempting to deny them the freedom to do that, while those who did not want to hear them could choose not to attend the talks.

A parallel situation occurred when a university in Texas attempted to shut down a student group’s planned drag night performance. Illiberal conservatives defending this made similar arguments that there was no need to have drag queens performing on a university campus and that students should not have this “forced down their throats”. This was another attempt to reframe the freedom issue and claim that the students who did not wish to see drag queens were having them imposed upon them. Again this can be responded to with arguments that other students did want to see them and that those who did not want to should simply do something else.

These arguments for harm and denials of interfering with freedoms are bad and easily refuted, but we should take some comfort from the fact that people are still trying to make them. For most people, there remains a fundamental discomfort with admitting to being authoritarian that results in attempts to defend illiberal actions on liberal grounds. This would not have been deemed necessary in the late medieval period. Nobody suggested, for example, that one should not criticise the king or government because it could cause people to try to kill him or anybody. One just did not criticise the king or government. That was “seditious libel” until 1689. Nor did anybody suggest that it wasn’t really denying women’s or the lower class’s freedom if they were not allowed to advocate on their own behalves in a public sphere or were otherwise denied individual autonomy. They simply had no right to any such freedoms and it was understood that they owed ‘faith and obedience’ to their fathers, husbands or masters. This is still the case in many cultures without a strong liberal tradition today.

The lack of consistent principle is both infuriating and worrying but the fact that people can and do still call on liberal principles when they need to does give some grounds for optimism. Even as illiberalism abounds and is quite evident in various kinds of arguments for censoring or constraining the freedoms of others, people still reach for the harm principle, reframe and appeal to the freedom principle and call upon evidence and reason when useful to do so. Liberal values remain culturally salient.

This is not to deny that we are seeing the rise of some openly authoritarian factions. There are people who will not try to pretend they are still defending freedoms and justifying coercion on the grounds of harm. There are Christian Nationalists who will simply state that non-Christians should be denied equal rights and equal access to the democratic process because they are not Christian. There are Islamists who will declare that those who insult or leave Islam must die. There are some who believe women should not be able to vote or have equal access to professions or pay because these are men’s roles. Others believe that black and brown people must be forcibly removed from a country because that country should be a “white homeland.” There are those who would recriminalise homosexuality on the grounds that it is against the will of God or simply unnatural or disgusting and those who would enforce sex-based dress codes and gender roles claiming that to do otherwise is ‘degenerate.’ And there are those who claim that simply being conservative or gender critical or critical of the Critical Social Justice movement is intolerable and that it is appropriate to respond to it with violence, while declining to make any case for harm and explicitly rejecting the value of freedom. These people are overwhelmingly regarded as extremists and we must make sure they remain so.

There are also some who will acknowledge that they are being illiberal but will claim that this is an emergency measure in response to illiberal wokeness and that it is necessary to restore a level playing field after which we can resume upholding individual autonomy. This is naive and inconsistent and can be argued against as such. Others may claim that we need to just be a little bit illiberal in order to protect liberalism (frequently misusing Popper’s Paradox). They are frequently the ones who wish to regulate sexuality and gender presentation or ban anything that could be considered ‘woke’ from knowledge-production institutions. It can be pointed out to them that whichever ideological faction gains prestige and power will be the ones able to determine in which direction it is acceptable to be a little bit illiberal and they should not assume this will never be the opposite one from their own preference.

On a broader societal scale, when people are being illiberal, they still instinctively frame their actions in liberal terms or feel a need to find ways to deny that they are illiberal. This indicates that liberalism still has significant cultural capital. Therefore, those who feel despairing that liberalism has died should take heart that it has not. Liberal intuitions and assumptions are still doing a lot of unacknowledged background work in our public conversations. We need to bring them to the foreground.

What can we do about this?

Liberalism is clearly not dead, but neither is it thriving. For much of our public discourse, it runs as a kind of background programme influencing everything we talk about, but not manifesting consistently in ways that facilitate productive collaborative conversation, the establishment of truth or the resolution of conflict.

In many ways, liberalism can be considered a victim of its own success. Although some people living in liberal democracies still remember egregious denials of their autonomy, for most of us, liberalism is something we’ve grown up expecting, not something we’ve had to fight for.

We haven’t had to convince society that we should be allowed to practise our own religion - or none - without prosecution. We haven’t had to argue for the right to criticise the monarch or advocate republicanism without being charged with treason. We’ve never needed to make the case for criticising the government, or for campaigning for different policies or a different government.

We’ve not had to persuade a sceptical public that working-class people or women should have a say in electing that government, or that Catholics, Jews, black people, women, or the working class should be able to attend university or enter professions.

We haven’t had to argue for the freedom to choose or leave our relationships, to decide how many children to have, or whether to have them at all. And few of us who have romantic or sexual relationships with people of the same sex have had to argue that we should be able to do so without being arrested.

When people no longer have to continually formulate arguments based on the principle that they should be allowed to believe, speak and live as they see fit, provided it harms no-one else nor denies them the same freedoms, they can all too easily forget how to do so. When liberalism becomes a default assumption, it ceases to be regarded as an active practice and becomes a passive expectation. This moves the action needed to fulfil that expectation outside of individuals and into a nebulous concept of ‘society.’ It is fundamentally hard to think of oneself as ‘society’ although that is, in fact, what we all are.

When liberalism becomes an assumption and an expectation rather than a set of principles and a practice, people retain the sense that they are supposed to live in a liberal society, but they think of themselves as the individual or group that has the right of protection from imposition rather than an active part of society that has the responsibility to uphold such protections. They then feel aggrieved when their own freedoms are threatened by one form of illiberalism or another and as though a liberal society has failed, rather than thinking of themselves as the liberal society that needs to respond to this with liberalism.

We are currently living with the consequences of no longer seeing the upholding of liberalism as a shared civic responsibility. When people have not had to practise liberalism consistently throughout their lives, they often lack a clear model of its principles or the ability to articulate them. Instead, liberalism is taken for granted, active maintenance of it ceases and it erodes. Historically, liberal freedoms were won because people did see them as a collective duty and upheld them across group lines, not only when they stood to benefit. Religious minorities gained equal rights because religious majorities supported them. Women won equal rights because many men stood with them. Racial minorities gained access to full civic life because racial majorities backed them. Sexual minorities gained freedom because heterosexuals defended it.

The problem we have now is that people still have enough of an intuitive sense of liberal principles to call on them as a tool when their own rights are threatened, but not a sufficiently conscious and well articulated model of liberalism to stand up for it in its own right and do so as a shared, collective responsibility.

This understanding of liberalism as a shared civic responsibility and an active practice is exactly what we need to reinvigorate. That begins with a sense of history and a recognition of our shared philosophical inheritance as the heirs of Western liberal democracy. In a culture increasingly dominated by postmodern and post-truth partisan narratives steeped in historical revisionism and divorced from both reality and consistent principle, we can choose not to follow suit. We can reject the postmodern and the post-truth, and reaffirm a meaningful and accurate concept of history - one that recognises the development of Western modernity and its commitment to truth, reason, and liberal principles.

We humans seem to need narratives to inspire and unite us, and this has always been a challenge for advocates of empirical, rational, and liberal thought. We lack the simple, satisfying stories of good and evil, meaning and destiny that religion offers or that fuel utopian, reactionary, or revolutionary movements. And yet, we do have a shared history and a philosophical inheritance that is, in truth, pretty inspiring! It is also, with complete accuracy, customisable.

For conservatives who value cultural integrity, history, and tradition, defending the philosophical heritage of liberalism is entirely consistent with their broader value system. For patriotic Americans especially - those who take pride in belonging to the only nation founded explicitly as a liberal democracy with a constitution rooted in the principle that each individual is born with equal rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness - this should feel like a natural alignment. And yet many on the right now reject liberalism outright, confusing it with forms of left-wing illiberalism to which they are rightly opposed. Meanwhile, a deeply illiberal, right-wing ‘post-truth’ populism is gaining narrative dominance and calling itself “conservative” while undermining the foundational principles of the United States and of Western liberal democracies more broadly. This should act as a call to action for principled conservatives to stand up and defend the liberal tradition as their own and inspire young conservatives to understand that conserving Western civilisation begins with conserving liberalism.

For progressives who value equality, inclusion, and pluralism, it should be clear that the most effective vehicle for these aims has been liberalism. The greatest advances for working-class people, women, and racial, sexual, and religious minorities have occurred in societies shaped by liberal principles. Yet many who see themselves as progressive have grown disillusioned, turning against liberalism itself in favour of postmodern cynicism, identity-based shame applied to both themselves and their countries and a corrosive suspicion of the very concept of progress. This should be a call to action. Principled progressives must reclaim the liberal tradition as their own and help a rising generation see that the best engine for genuine social change has always been liberalism.

The inhabitants of liberal democracies - beneficiaries of the Enlightenment and the liberal philosophical tradition - have a vested interest in understanding liberalism as a shared inheritance that protects the freedoms we all value. This inheritance was hard-won: the product of centuries of struggle to replace divine authority and rigid hierarchies with individual autonomy, evidence-based epistemology, reasoned debate, and respect for our shared humanity. Liberalism is the framework that allows us to think freely without coercion, disagree productively, resolve conflict without violence, and reform without tearing society apart. If we want to conserve what is worth keeping and change what needs changing, we need liberalism as both the foundation and the method. It is time we stopped treating it as background noise and made it the conscious practice of our civic and political life once again.

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has over 5000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.75% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2025 is to increase that to 7%. This will enable me to keep doing this full-time into 2026! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

Helen - I've followed you on and off since crazy 2020 Twitter days, and I've long appreciated your principled idealism. (Liberalism fundamentally entails optimism, after all.) I'm not sure how to describe it exactly, but you always manage to strike a tone that is both resolute and *kind*. A true balm for the soul amidst all the online discourse.

Do liberals delete posts? Like the last 5 hours of posts?

I thought only Soviets did that?