Why Apologies Matter

Trump, dogs, the liberal order.

(Audio version here)

The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain has over 6000 readers! We are creating a space for liberals who care about what is true on the left, right and centre to come together and talk about how to understand and navigate our current cultural moment with effectiveness and principled consistency.

I think it is important that I keep my writing free. It is paying subscribers who allow me to spend my time writing and keep that writing available to everyone. Currently 3.8% of my readers are paying subscribers. My goal for 2026 is to increase that to 7%. This would enable me to write full-time for my own substack! If you can afford to become a paying subscriber and want to help me do that, thank you! Otherwise, please share!

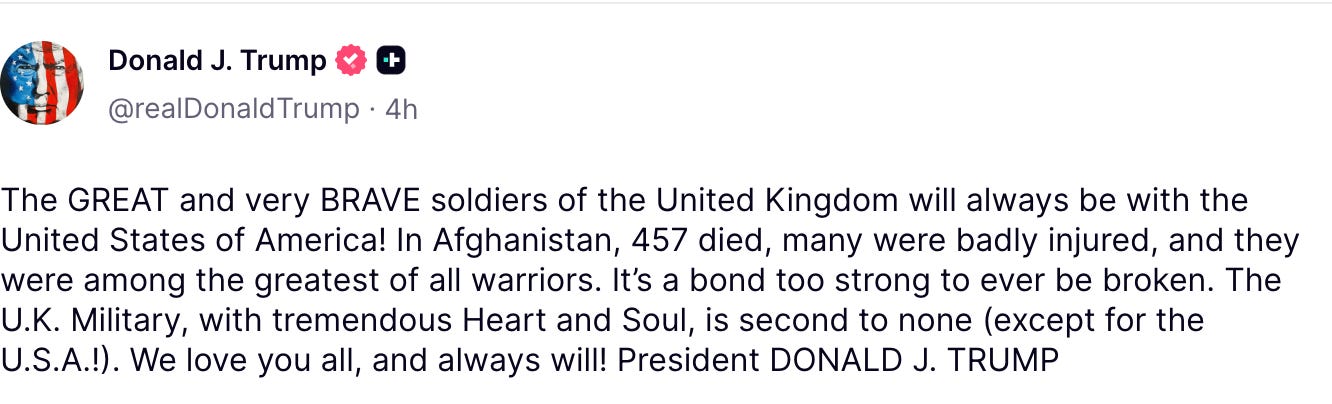

The UK is currently unusually aligned on an issue across political divides. That issue is the position that Donald Trump should apologise for having said that he was “not sure” that other countries in the NATO alliance would ‘be there if we ever needed them.” He added that, while they would claim to have responded to the US’ call following the 9/11 atrocity and fought alongside the US in Afghanistan, they ‘stayed a little back, a little off the front lines.”

This is, of course, not true. The only time Article 5 of the NATO agreement has been invoked was by America on that occasion and allied forces responded, typically sustaining higher casualties than US forces. UK and Canadian forces were recorded as suffering four times the numbers of deaths as US forces at one point with the highest fatality rate per capita being suffered by Denmark. (From Fraser Nelson’s excellent overview of this here).

Following this false and insulting claim made by the President of the United States, political leaders on both the left and right across Europe have been united in objecting to it. Keir Starmer described the comments as “appalling and insulting” and worthy of an apology. Injured veterans and relatives of British soldiers who died in Afghanistan have likewise demanded a retraction and apology.

The President has since offered what functions as a reversal of his former statement in the case of the UK, but not an apology. The fallen soldiers of other allied countries remain unrecognised.

Why do apologies matter so much to us? They are just words. Often, just one word - “Sorry.” It costs nothing in material terms and effects no material change in itself. Yet, apologies are very important to us. Political leaders demand apologies and even make them for historical events which no living person was involved in. Major news outlets report apologies from both influential individuals and institutions. It is common for people to express the view that simply desisting in a behaviour is not sufficient - it must also be apologised for. I hear this most often in relation to the Critical Social Justice movement, particularly in the realms of trans activism and “anti-racist” activism right now, but it is also commonly expressed about not only other political movements, but interactions of all kinds on both structural and individual levels.

An apology is not simply words expressing regret. It functions as a reset and a re-establishment of an acceptable order or state of being. It says not merely, “I feel bad about that” but “I recognise that what I said or did was wrong and consequently I will not do that again.” Such acknowledgements are very important to our social species whose survival and thriving has depended on being able to trust those with whom we cooperate.

Humans are not the only species of social mammal which has the concept of an apology. Dogs and canids more broadly also have a simpler form of ingrained ‘apology’ behaviour. They bow. Somebody who has accidentally trodden on a dog’s tail and instinctively turned to say “Sorry!” and ruffle the animal’s ears could be forgiven for believing that dogs don’t require apologies by the speed with which they ‘accept’ them and hasten to reassure you with their body language that you need not give it a second thought. They would be wrong.

Because wolves and consequently dogs engage in rough and tumble play as a form of social bonding and exercise, they frequently accidentally hurt each other. Because all members of the pack engage in this and they are also hierarchical pack animals who enforce or challenge hierarchy with displays that include aggression, they need a way to signal that aggression is not what they just intended. Therefore, when one dog accidentally hurts another in play, s/he will typically ‘bow’ immediately to indicate that it was an accident. The other dog will typically respond with friendly open-mouthed ‘smiling’ and wagging body language. A failure to make this apologetic gesture will often result in a dog being shunned by the pack. It has become a threat to the social order.

If the dog who has accidentally hurt another is subordinate, it is saying, “Oops! Don’t read anything into that! I respect your position!” and the dominant dog is responding, “All good. Don’t worry.” If it is a dominant dog, it may not ‘apologise’ but very often it will and then it is saying, “I didn’t mean to do that. You haven’t done anything wrong” and the subordinate dog is responding, “Thank you for the reassurance. I also don’t want to fight you.” This is also what you are communicating as a human if you apologise to a dog for accidentally hurting it and what its enthusiastic acceptance indicates. (It is important to reassure your dog in this way so that it does not become anxious and uncertain of its place as it could then become either aggressive or fearful. I am rather nerdily read up on this having fostered dogs with behavioural problems).

Ultimately what dogs (and wolves) are doing when they engage in this “apology bow” ritual is communicating reassurance that nothing has changed in the social order and that bonds of trust and alliance are still intact following an incident which could potentially read otherwise. They are restoring order and affirming secure relationships. This is also what humans are doing, but in a far more morally complex and multifaceted way.

We could consider there to be three levels of apology although you could also break it into many more subcategories if you were so inclined. (British and Canadian politeness habits of beginning sentences with ‘Sorry’ without actually having anything to apologise for should be recognised as just that - a habit. It simply means that when we actually want to convey regret and culpability, we have to use more words).

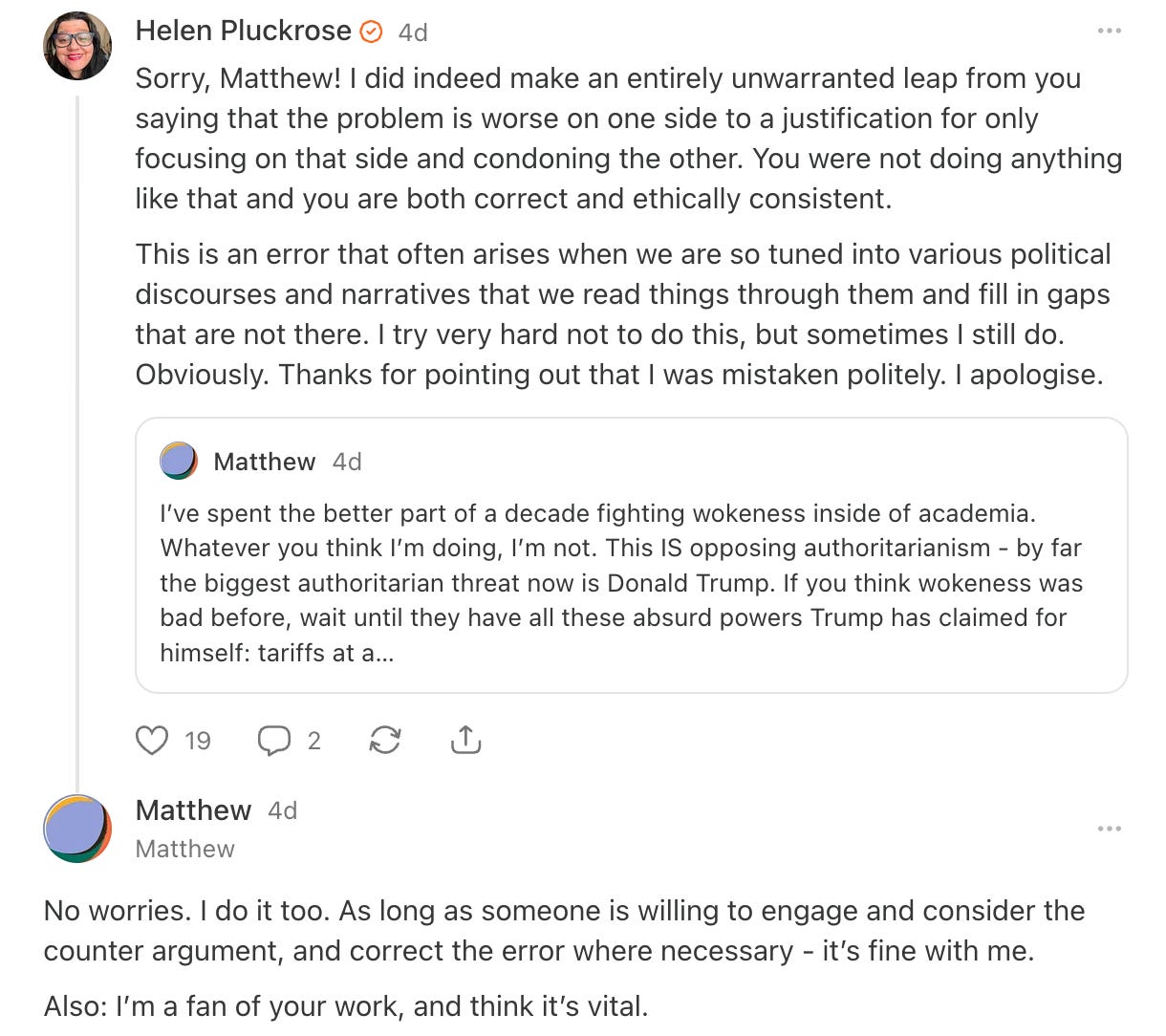

On the most simple and forgivable level, a human “Sorry” can be the same as those of dogs and convey “I did not mean to do that, but I am responsible for it.” It can cover very innocent things like accidentally bumping into someone or getting someone’s name wrong to more potentially hurtful things like forgetting a friend’s birthday, or an appointment or mispeaking in a way that could be taken as rude or otherwise clumsily but unintentionally causing somebody else minor inconvenience or mildly hurt feelings. This is the kind of culpability for which we expect reasonable people to accept apologies, because it was a human mistake to which we are all prone. People generally do accept these kinds of apologies immediately and appreciate them having been made rather than excuses or ignoring the minor transgression. I had one of these recently, when I misread a substack post and responded to something the other person was not saying. My apology was received warmly and this individual may well regard me more positively now than he did before my mistake.

It is significant that in his response to Trump’s statement and despite using the words ‘appalling’ and ‘insulting,’ Keir Starmer framed asking Trump for an apology in such a way that made it clear that he was willing to interpret the claim as this kind of mistake and consequently respond to it as such. He said, “If I had misspoken in that way or said those words, I would certainly apologise.” His intention by putting the statement in the category of the kind of clumsy error we might all make was almost certainly diplomacy to make it as easy as possible for Trump to apologise while saving face.

The next level of apology I would suggest, is a more explicit acknowledgement of a moral failing that requires genuine regret and remorse and a commitment to non-repetition, but one which is not defining of the individual or an institution. It could be considered behaviour that is out of character or that represents a temporary lapse in judgement. It could be impulsive words or actions done in the ‘heat of the moment’ or be what we mean when we say to someone at risk of losing their temper, “Don’t do/say anything you will regret.” It could be a failure to live up to one’s own values while under significant pressure or a bowing to peer pressure. It could be developing an addiction or becoming radicalised into a movement. The individual knows what they are doing and is fully responsible for it, but it is not defining of their character.

Following the death of my father, I experienced very volatile moods including bursts of anger that led me to behave unreasonably and lash out at my friends, taking offence at innocent things and insisting that they did not care about me and had no place in my life. I think it felt abominable to me for people to be carrying on as normal when my father was dead and I felt adrift. I offered sincere apologies for these within a few hours and my friends, while not very happy about it and insisting I saw a counsellor to deal with my grief, were forgiving and I still had all of them at the end of it. This was not defining of my character but I was still responsible for recognising it, apologising for it and addressing it. Provided it is addressed and this is not a persistent pattern, such lapses in judgement can and should be forgiven and moved past.

Because we have all done things we regret and failed to live up to our values at times, most people are generally quite forgiving of lapses of moral judgement too, provided they are acknowledged as such and intentions not to repeat it are expressed sincerely. They can be regarded as a swerving off course which can be corrected and consequently still as a ‘mistake.’ We often hear this word used when somebody is revealed to have said something reprehensible on social media in their past or got sucked into a radical ideology they since extricated themselves from or even committed a crime through impulsive foolishness rather than as part of a pattern of anti-social behaviour - “Don’t ruin his/her life because of one mistake.”

This kind of wrongdoing can also apply to institutions and political movements which appear to have gone off the rails, lost their mission and be in need of course correction. They can engage in ideological overreach overcorrecting for their opponents’ overreach, act in ways that go against their stated principles, make bad leadership choices, allow extremists to have too prominent a voice or veer into condoning authoritarianism. If allowed to continue along these lines, it will become defining of their character, but they have the option to recognise their failings, acknowledge and apologise for them and self-correct and we should retain hope and expectation that they will do so. In the case of political sides, we very much need liberal leftists and ethical conservatives to address the extremists on their own sides and marginalise them to the fringes so that the “character” of neither “the left” nor “the right” is defined by illiberal identitarians. With regards to the Trump statement, I would suggest that this kind of apology would be warranted. Denigrating the memory of fallen soldiers fighting for one’s country is certainly out of character for ethical conservatives.

The third level of apology is the one which is hardest to accept because it involves addressing consistent and persistent patterns of inexcusable behaviour that do seem to define somebody’s character or that of an institution. They involve consistently behaving in ways that harm other people with no acceptance of responsibility. No amount of apology at this stage can meaningfully undo the harm that has been caused and promises of reform will necessarily and self-protectively be regarded with skepticism for a considerable time, if not forever. Nevertheless, people (and institutions) can redeem themselves by sincerely recognising that their behaviour has been harmful, feeling genuine and appropriate remorse, taking responsibility for it, honestly understanding and addressing the causes of it in themselves and committing to never repeating it. Again, we should always hold out the hope that they will do so and seek to facilitate this.

Even when behaviour is absolutely reprehensible and extremely difficult to forgive, we still have a strong desire to hear an apology made sincerely. This need for acknowledgement of wrongdoing and expression of regret is, it seems, absolutely essential to the human psyche and on all levels.

I recently spoke to a woman whose parents had been extremely and unambiguously abusive. Nothing they could do now would restore her childhood or undo the difficulties she now has with her self-esteem and relationships. She ran away when she was 14 and, now nearly 40, has no regular contact with them, but she gets in touch sporadically in the hope that they will acknowledge that they were abusive and apologise for it. They do not. She said “I don’t want a relationship with them and I don’t want to punish them. I just need them to acknowledge it. Then I could make peace with it.” This is a consistent human desire. People who have been in abusive relationships or one in which there was serial infidelity which they do not forgive still have a fundamental need for their former partner to accept responsibility for it and apologise. People whose children have been murdered and who are never likely to forgive their killers or accept an apology still want to know that they acknowledge what they did and are sorry for it. On a deep psychological level, we need to feel that a moral standard exists, has been acknowledged and responsibility has been taken to be able to move on.

This is true on an institutional level too. Even when an official apology cannot repair any material harm done and no individual can be held responsible for that harm, we still feel a psychological need to set the record straight and acknowledge wrongdoing in order to restore some kind of moral order and rebuild trust. It can be of no comfort to Alan Turing who (probably) committed suicide in 1954 that the government issued a formal apology in 2009 for persecuting him on the grounds of his homosexuality in response to a public petition. Nevertheless, offering one establishes an affirmation of a moral order in which such treatment of gay men is unacceptable and never to be repeated. Finland’s 2000 apology to the Jewish people for allowing the extradition of Jews to Germany in 1942 cannot restore lives. It can only repair trust that this was acknowledged as morally unconscionable and must never happen again. Likewise, Bill Clinton’s apology for European Americans role in the Transatlantic slave trade in 1998 serves only as a recognition of historical collective wrongdoing. (An interesting list of political apologies can be found here).

If Level One of apologies is “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to do that”, Level Two is “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to behave like that. That is not who I am” and Level Three is, “I’m sorry. That is who I was and I recognise that it was wrong. I will not be that person (or kind of institution) again.” In all cases, an apology is not simply a word or a gesture. It is a reset and affirmation of a shared moral and social code ranging from a simple clarification of clumsy error to a profound commitment to fundamental change. Like dogs, the social mammals known as Homo Sapiens require it to restore social order and enable trust, cooperation and dependable alliances within everything from small friendship groups to international relations. On all levels of engagement, we still think with the psychology of big brained social mammals living in troops whose survival and thriving depends upon our relationships with each other and reliable systems of cooperation.

Therefore, when the political leader of one country sets out an expectation of an apology from the leader of another, this is not a matter of etiquette but an indicator of a serious international incident. He is conveying, “I am afraid you are presenting a threat to international order and require you to reaffirm that we still have a bond of trust, cooperation and an alliance.” This is a risky manoeuver because a failure to provide that can be read as “Yes, I am that kind of threat and no, I do not affirm that bond.” Trump clearly recognised this and his response can be seen as an affirmation of the bond, preventing an outright breakdown of relations. However, without an apology, there is no recognition of wrongdoing and no commitment to not repeating such statements, and trust is damaged. Relations remain tense. If Trump does take steps that fracture the Western alliance (such as invading Greenland) or otherwise unambiguously damages international relations and Americans later take democratic action to prevent this from continuing and elect a government that seeks repair, the new government will likely have to issue an apology for actions taken under the Trump administration even though they personally were not responsible for it.

Apologies that are offered willingly with the intention of affirming commitment to a shared moral code are clearly very important, but what about when they are not offered willingly? Does this change the dynamic? I think it clearly does. Apologies then become a capitulation to power, cannot be considered sincere, cannot re-establish trust and do not shore up cooperative alliances.

When my daughter was tiny, my best friend had a daughter of the same age and we worked part-time around each other’s hours and looked after each other’s girls. Consequently, they grew up almost as siblings spending every day with each other and each mother had the right of ‘laying down the law” to both girls! We disagreed on the issue of making them ‘say sorry’ if they had misbehaved. To my friend, this was simply teaching them manners and expecting them to take responsibility for bad behaviour. To me, this was coercing them into a lie. (One could not look at little, red faces of fury grudgingly forcing out the word ‘sorry’ and believe that was, in any way, sincere). I said that my friend could absolutely tell my daughter that if she behaved badly she would not be able to join in with fun things or would have to go and be on her own until she could behave well, but not to compel her to express feelings she did not have. I found that once the tantrum had cooled down, they would generally naturally wish to restore their friendship with a ‘sorry’ and that this was much more meaningful.

I believed then that a forced apology was coercing a child into affirmation of a moral orthodoxy and not a good value to instill into a child. However, telling her “You can lie on the floor and scream and throw things if you want but you’ll have to go and do that in your room because we are playing and having fun down here and you’ll be in the way” did not compel her to affirm anything but simply recognise that if one wants to be included in fun, social things, one has to behave in prosocial ways and consider other people. My friend disagreed with this approach and believed in instilling more deference to authority. Although I did not relate this to politics at all at the time, I thought of this later when discovering Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory and recognising that my friend was what we would call “A small c conservative” while I was a left-wing liberal. We vote differently. We are still good friends. Our girls are now in their early twenties and both delightful and well-adjusted young humans and assets to society!

Coerced apologies have also been a recurring feature throughout history, however, and the impacts of these have been more damaging. Whether this took the extreme form of the Catholic Church forcing heretics to publicly ‘recant’ their views and do penance or Maoist “Struggle Sessions” or the Critical Social Justice movement wringing public apologies out of people as part of Cancel Culture, these cannot be said to build trust, cooperation and healthy alliances. An apology is only a moral act that builds trust and bonds if it is freely given. If forced, it becomes a loyalty ritual, and loyalty rituals belong to authoritarian regimes, not liberal ones. People living under authoritarian regimes are fearful and distrustful and while rebellion may be able to be suppressed for considerable time, resentment accumulates until ruptures are catastrophic.

Forcing apologies, therefore, subverts the bonding and ordering process that humans evolved the drive to seek and accept apologies for. Further, apologies extracted in this way are frequently distrusted for good reason and not accepted. It became common during the height of “Woke” Cancel Culture for people to urge others not to apologise if singled out by activists of the Critical Social Justice movement. This simply did not resolve the issue because activists would then find ways to ‘problematise’ the apology and find more evidence within it of the individual’s “guilt”. Careers and reputations were destroyed this way. It was much better strategically to say nothing at all and hope that the mob became bored and its attention passed on to someone else without doing too much damage. Even if somebody had said something genuinely racist, sexist or homophobic that they regretted and wished to acknowledge to have been wrong and commit to not repeating, it was in their personal interests to ignore or double down on the moral failing rather than apologise for it.

This is clearly a terrible way to go about trying to create social order and achieve progress which horribly corrupts the function of apologies, damages trust, disincentives forgiveness, reconciliation and cooperation and builds resentment and vengefulness. A liberal society is one in which apologies are not coerced either legally or socially and so can be understood to be given willingly and trusted to be a sincere commitment to upholding the values one shares with one’s friends, community or wider society and not repeating the wrongdoing. A healthy society is one in which we are open to accepting sincere apologies and supporting those who have behaved badly in large or small ways to stick to their commitment not to do so anymore by forgiving them and allowing transgressions to be overwritten by consistent demonstrations of ethical and prosocial behaviour.

Apologies matter because human cooperation depends on signals that restore trust. They are not simply a matter of manners or etiquette or social performance. As social mammals, we have a hardwired need for signals and a need to have good reason to trust them to be sincere. Whether it takes place between a romantic couple, a family, within a friendship group, within a larger community, between different factions of a society or on the level of geopolitical alliance, apology is a mechanism by which we reaffirm our shared values, bonds and alliances and the moral order we intend to uphold. This is the case whether a transgression is a clumsy mistake, a lapse of judgement or entrenched wrongdoing. They all require a voluntary acknowledgement of wrongdoing.

When apologies are given willingly and can be taken to be sincere, relationships of all kinds and on all scales become stronger, more trusting and more reliable. When they are coerced, those relationships become fearful, distrustful and fragile. Shared values become performative rather than binding, secrecy and resentment build, and ruptures are inevitable and extremely difficult to repair. If they are not given at all, trust breaks down utterly and reconciliation, repair and cooperation become impossible.

This is why Donald Trump’s apology for his statement about NATO allies matters and why his commitment to respecting the liberal democratic order of Western Civilisation and Western alliances matters more broadly. It is a fundamental measure of trustworthiness from the leader of the nation most explicitly founded on liberal democratic principles. But the issue is far larger than one crass and grossly insulting statement by one president of one country. He is one individual who only temporarily represents the United States of America and his statement is one symptom of an illiberalism that is rising in many more forms and in many more quarters.

We are, in effect, in a political version of Level 2: the point at which a society has swerved off course but has not yet fully changed its character. Western liberal democracies still possess liberal principles as their foundations, but illiberal factions have grown prominent enough that those principles are being rapidly eroded and this is in danger of becoming ‘the new normal’. This is the moment at which people who value liberal democracy must consciously recognise liberalism as a higher-order value and engage in collective self-correction. We can still say, “This is not who we are.”

If we fail to act at this point and illiberal factions come to define us, we will have crossed into Level 3 where an illiberal mess is what we are and returning from that is vastly more difficult.

Liberal societies cannot survive without the shared commitment to liberal principles that enable sincere apology and sincere forgiveness because both depend on the freedom to commit willingly to moral standards that enable self-correction and effect reconciliation. If we can preserve that freedom, we can preserve the possibility of cooperation, from the smallest friendship to the largest alliance.

Dogs are much better people than humans. I agree with everything here, but without any shared moral compass and with the new weapon of online hounding, I fear we lack the right instincts to mend our social fractures. Trump represents the rejection of social "niceties," as his fans might put it, or basic human decency and honor as many of us see it. I accept that he won the elections and I agree with some of his policies, but his telos is the law of the jungle, not the harmony of the pack. Whether our fragile and overstretched social order can withstand his rabid bravado and chaos remains to be seen. Along with many Americans I am mortified by this latest in a long line of reprehensible remarks. Sorry.😞

From personal experience, I find your linking here of the concepts of ‘sincere apology’ and ‘sincere forgiveness’ reminds me that we can choose to practise both silently within our own hearts in order to ‘reset’ our sense of ourselves as an essentially well-meaning, lovable yet fallible human being, in circumstances in which those who our consciences urge us to apologise to are already deceased or ‘lost’ to us in some other way. Thank you for this reminder.